In Luke Fildes’ classic painting of a family doctor engaged in watchful waiting over a child’s sick bed, the doctor is pictured as somebody whose work of caring for his patients does not end after he reaches the limit of what can realistically be achieved with more medical intervention. It just takes another form. In the painting, it forms as compassionate endurance shared with the child’s parents, of time that has become unbearable for all of them. In the contemporary world of NHS healthcare however, the forms that endurance can take are likely to be less romantic. Yet to wait, to stay and to endure in healthcare work, is evidently still necessary. Pandemic stories about the NHS have celebrated the fantasy of a totally efficacious, durable workforce. But they have also tended to overlook the ordinary ways that patients and practitioners have gone on suffering through different stages of carrying on amidst ongoing states of crises.

In general practices, the chronic or self-limiting nature of so many of the cases that make up a typical workload can mean that durational practices like waiting can be practical methods for working with the materialities of ill health that are either too temporary, or too tenacious to intervene in. Beyond the clinical realm, the National Health Service is a project which for years now has been as much a source of grievance as it has been a source of hope and purpose for those who have an attachment to it. Staying and enduring in this setting could simply describe the experience of going on for longer as an NHS general practice worker, and the exhaustion that comes from having to carry such a project and make it dependable for others.

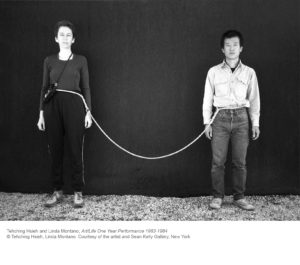

This thesis aims to grasp the temporal modes of care that are helping to support life in the wake of a permanent state of crisis in the NHS. It does this by making cases out of unheroic practices of waiting and enduring coming out of general practice during the first year of the pandemic. In these cases, to care without the expectation of an event often means to persist in holding on to what feels worthwhile about a care arrangement, though without necessarily knowing where this will lead or whether this is sustainable. In contrast to how conventional medical cases are used as a way of demonstrating how to make progress out of care, they show general practice to be a site where the very possibility for care can rest on the willingness of patients and practitioners to refuse the categories of epic and heroic, in favour of finding other ways of getting through.