WHERE IS THE PLANETARY? Video recordings are now available.

In October 14-17th, 2022 Lisa Baraitser participated in the series of events about the planet organised in Berlin by collective of scientists, scholars and artists.

The recordings of talks and events are now available:

WHERE IS THE PLANETARY? DAY 1

The first evening of Where is the Planetary? set up the search for a model of sustainable collaboration under planetary conditions: What diverse worldviews underlie the way we deal with the planet’s crises? How can a common political and social agency emerge from this? In an experimental setting designed by artist Koki Tanaka, scientists, scholars and artists shared various perspectives on planetary practice: from zooming out to the cosmic, grounding back to our geological Earth and personal biographies, to exploring the ethics of repair and care and the vision of a second primordial soup for planetary survival.

WHERE IS THE PLANETARY? DAY 2

On the second day of Where is the Planetary?, the search for a common planetary practice became tangible. The five research questions were linked to a series of activities. The idea of a “primordial broth” served as inspiration for a jointly designed recipe for the conditions of planetary habitability. By accumulating and recomposing ideas and material from cultural production and the built environment, participants posed questions about what needs our care, what should be preserved, and what should be left behind. Equitable, scalable processes of negotiation and deliberation were discussed into literal exhaustion. Collaboratively, participants wrote a sort of planetary script. All of this happens embedded in a film shoot led by Koki Tanaka. The running camera co-determined the course of the day.

MLA Convention 2023: Samuel Beckett Society Panel, Sunday 8 January (Virtual)

This year’s MLA Convention is being held in San Franciso, California from 5-8 January, and continues the recent trend of combining in-person and on-line panels. The annual Samuel Beckett Society panel will be held virtually and can be accessed world-wide by those registered for the convention. The panel, which will take place at 8:30 to 9:45 PST promises a particularly rich discussion under the rubric Beckett and the Work of Care featuring the following participants:

Elizabeth Barry (University of Warwick]: ‘The Salvation Army Is No Better’: Beckett, Aging, and the Ambivalent Work of Care.

Swati Joshi (Indian Inst. of Tech., Gandhinagar): Caring Nurses and Nursing Care in Beckettopia

Molly Crozier (U of Liverpool): Care, Need, and Gendered Labour in Endgame and Happy Days

Laura Salisbury (U of Exeter]: Waiting for Beckett: Suspended Time as the Work of Care.

The panel will be chaired by Feargal Whelan (Trinity College Dublin).

More details about the convention are here.

Save the Dates, The Time of Care, A Waiting Times Conference – Tuesday 28th – Wednesday 29th March

We would like to invite you to save the dates for our end-of-grant hybrid conference: The Time of Care: Conclusions from the Waiting Times Project. The event will take place on Tuesday 28th March – Wednesday 29th March 2023, together with a special show by renowned performance artist, Martin O’Brien, to open proceedings on the evening of Monday 27th March.

Waiting is one of healthcare’s core experiences. There from the time it takes to access services; through the days, weeks, months or years needed for diagnoses; in the time that treatment takes; and in the elongated time-frames of recovery, relapse, remission and dying. However, though often discussed and considered in terms of waiting lists and times, and especially in relation to health and social care crises, waiting is also vital to practices of care.

Waiting Times has explored what it means to wait in and for healthcare by examining lived experiences, representations, and histories of impeded and delayed time. The project has mobilised a range of artistic and engaged research methodologies, as well as ethnographic, philosophical and historical investigations to consider different forms of suspended, elongated, and “non-productive” temporalities in different sites and practices: in forms of watchful waiting and recurrent waiting with that take place in general practice, mental health services, and trans care; within modes of chronic care and forms of time that are held and unfolded within psychotherapy; and as part of cultural framings, experiences, and care provided at the end of life.

The conference offers a final chance for our researchers to showcase their work, to reflect collectively on its meanings and implications, and to bring the team into conversation with invited speakers and research partners across a number of panels and performances.

We would be very keen for you to join us for these interactions, either in-person (at the Friends’ House, Euston Road, London) or online.

Registration will open very soon, and we will share the Eventbrite link once our page is live. Attendance is free, and there will be no cap on online attendance. Our in-person capacity will be limited, however, and spaces will be made available in due course.

We (somewhat ironically) can’t wait to share this time with you and we very much look forward to seeing you in some capacity in March!

The Waiting Times Team.

PSYCHOANALYSIS FOR THE PEOPLE: FREE CLINICS AND THE SOCIAL MISSION OF PSYCHOANALYSIS, the special issue of Psychoanalysis and History, Volume 24, Issue 3, December, 2022

The new issue of Psychoanalysis and History is dedicated to free clinics and the social mission of psychoanalysis is now published online, available to read and download! Click here to get access to all articles.

From the Bariatric Clinic – Dialogue between Dr Anuradha Menon and Prof Lisa Baraitser, 5 December 2022

The history of human obesity is complex. Modern Bariatric services offer medical and surgical interventions towards what proves a challenging task for both patient and clinician – that of encouraging sustained, substantial weight loss over a lifetime. Psychological approaches within bariatric services have a place not only in supporting treatment before and after surgery, but also in those who choose lifestyle modification over surgery. However, the focus of evidence-based approaches in healthcare settings is time-limited; and predictably on weight loss as the main desirable outcome rather than an exploration of the totality of the obese patients’ experience. Today’s Maudsley lecture is an attempt to address this gap by exploring the setting and frame of a Bariatric service from a psychoanalytical perspective. Dr Anuradha Menon who is a liaison psychiatrist and psychoanalyst working in a Bariatric service in Leeds will be in dialogue with Professor Lisa Baraitser, a psychoanalyst who has written widely on feminist theory, motherhood, ethics, care and temporality.

The history of human obesity is complex. Modern Bariatric services offer medical and surgical interventions towards what proves a challenging task for both patient and clinician – that of encouraging sustained, substantial weight loss over a lifetime. Psychological approaches within bariatric services have a place not only in supporting treatment before and after surgery, but also in those who choose lifestyle modification over surgery. However, the focus of evidence-based approaches in healthcare settings is time-limited; and predictably on weight loss as the main desirable outcome rather than an exploration of the totality of the obese patients’ experience. Today’s Maudsley lecture is an attempt to address this gap by exploring the setting and frame of a Bariatric service from a psychoanalytical perspective. Dr Anuradha Menon who is a liaison psychiatrist and psychoanalyst working in a Bariatric service in Leeds will be in dialogue with Professor Lisa Baraitser, a psychoanalyst who has written widely on feminist theory, motherhood, ethics, care and temporality.

Chaired by Simon Harrison and Emma Hotopf

Anuradha Menon is a Member of the British Psychoanalytic Society and has an analytic practice in Leeds. She also works part time as a Consultant Psychiatrist in Medical Psychotherapy and Liaison Psychiatry in the Leeds and York Partnerships NHS Foundation Trust and leads the psychological service offered by the Specialist Weight Management Service (SWMS), a Tier 3 regional service for Bariatric patients seeking medical and surgical treatments for Obesity.

Lisa Baraitser is Professor of Psychosocial Theory in the Department of Psychosocial Studies, Birkbeck, University of London, and a Psychoanalyst and Member of the British Psychoanalytical Society. She is the author of Enduring Time (Bloomsbury, 2017) and Maternal Encounters: The Ethics of Interruption (Routledge, 2009) and has written widely on feminist theory, motherhood, ethics, care and temporality. She currently co-leads a Wellcome Trust research project on waiting in relation to healthcare.

Recording available for 1 week to all registered participants

New paper: ‘What about the coffee break?’ Designing Virtual Conference Spaces for Conviviality.

Reflections from the ‘Material Life of Time’ conference team regarding online networking, engagement, and overall success of the online conference by Michelle Bastian, Emil Henrik Flatø, Lisa Baraitser, Helge Jordheim, Laura Salisbury, Thom van Dooren

Short Abstract

Online conferences provide one avenue for potentially reducing academia’s carbon footprint. Their widespread take up is accompanied by concerns that they cannot provide adequate alternatives to the face-to-face, particularly in terms of building new networks. This paper reports on The Material Life of Time conference and the success of our efforts to plan explicitly for conviviality.

Full text is available here.

PPNow 2022 Insiders and Outsiders: Navigating identities and divisions inside and outside the consulting room. 11-12 November, 2022

This conference considers divisions between the ‘internal’ and the ‘external’, what is ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ the psychoanalytic profession and practice, and how we might take more of a psychosocial and intersectional perspective in psychoanalytic work.

PPNow 2022 will open with a public lecture by Dr Noreen Giffney on the evening of Friday 11 November, followed by a full programme on Saturday 12 November.

Saturday 12 November Professor Lisa Baraitser will give a talk ‘On being with others ‘now’’.

Registration and details are here.

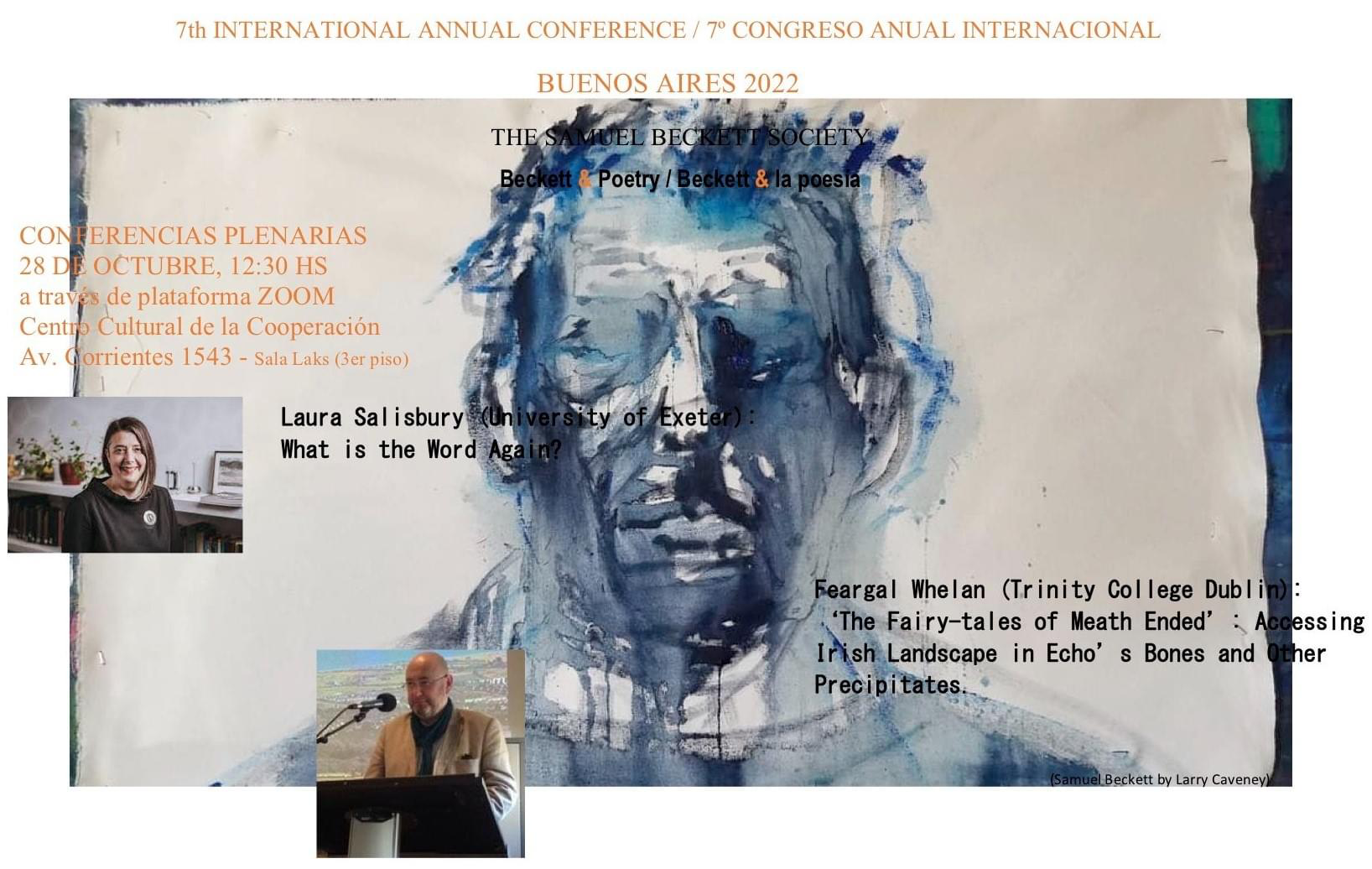

Beckett & Poetry/y La Poesía: 7th Annual Conference of the Samuel Beckett Society. Buenos Aires, 26-28 October 2022

The 7th annual Conference of the Samuel Beckett Society takes place this week in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Taking Beckett and Poetry as its theme, the conference will allow for an exploration of Beckett as a poet and the broader themes of poetics within his oeuvre. The event includes papers in English and Spanish further enhancing the opportunities for broadening interest in the Spanish-speaking world developed through the Society’s previous conferences in Mexico City (2018) and Almería (2019).

Laura Salisbury will present a keynote paper ‘What is the Word Again?’

Other keynote speakers include Daniel Caselli (University of Manchester], Ulrika Maude (University of Bristol), José Francisco Fernández (Universidad de Almería), Patrick Bixby (Arizona State University), and Feargal Whelan (Trinity College Dublin)

The conference is organized by the Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires and CEAMC (Fundación Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Música Contemporánea) under the stewardship of the indefatigable Lucas Margarit.

Full details of events and the complete conference programme are available here.

Where is the Planetary? A series of events about the planet. Berlin, October 14-17th

|

||

|