Martin Moore writes:

It is something of a foundational belief in the Sociology of Scientific Knowledge (and related fields) that knowledges are always shaped by the context within which they are constructed. Scientific knowledges are thus never independent of the social relations, economic structures, political pressures, ideological and tacit practices from which they emerged, and they are themselves cultural artefacts.[1]

Historians work with similar understandings about historical knowledge. Though articles or monographs do not routinely include historicisations of their own origins (though, note feminist histories like that by Catherine Hall and Carolyn Steedman), historians will usually recognise the circumstances of their text’s production in their acknowledgements.[2] Here they raise to the level of consciousness funding sources, intellectual interlocutors, social relationships and even some biographical detail to help make sense of where a particular work has developed.

This is not to say that historians work unreflexively in relation to their origins, nor that they never publicly look to contextualise their own knowledge. Rather, they have tended to reflect most heavily on the relationship between past and present in historiographical and methodological texts.[3]

Recently the Waiting Times team has been thinking about how the current pandemic has been reshaping relationships to time (and care), which we will be sharing in a forthcoming dossier on COVID-19. It was in this context that I was reminded about E. H. Carr’s famous suggestion that history was an ‘unending dialogue between the present and the past’.[4] As historical and social subjects, in other words, historians are just as much a product of their particular time and place as those they write about, and our interpretations of the past will be inescapably influenced by our biographical, social and cultural relations.

Broadly speaking, historians have tended consider the relationship between the present of scholarship and the history produced in terms of large-scale social, economic and political formations and trends. How has a historian’s position in the social field shaped their view of the past? How might experiences of particular events or existence within specific cultural and political milieu shape the questions that are asked within research?

Regardless of how long the current measures of containment, delay and mitigation last, the impact of COVID-19 on psychosocial, economic and political life will likely be profound, and thus so will its effects on historical scholarship. Although it might be folly to think about precisely what these effects will be whilst we are still in the midst of the crisis – of a moment that might be an historical rupture and beginning of a new normal, or prove to be something far less monumental – it is nonetheless possible to consider how historical scholarship is already being reshaped. To explore how COVID-19 is already making history.

*

Perhaps the most overt ways in which the pandemic is influencing scholarship is in terms of disruption to intellectual networks and project temporalities.

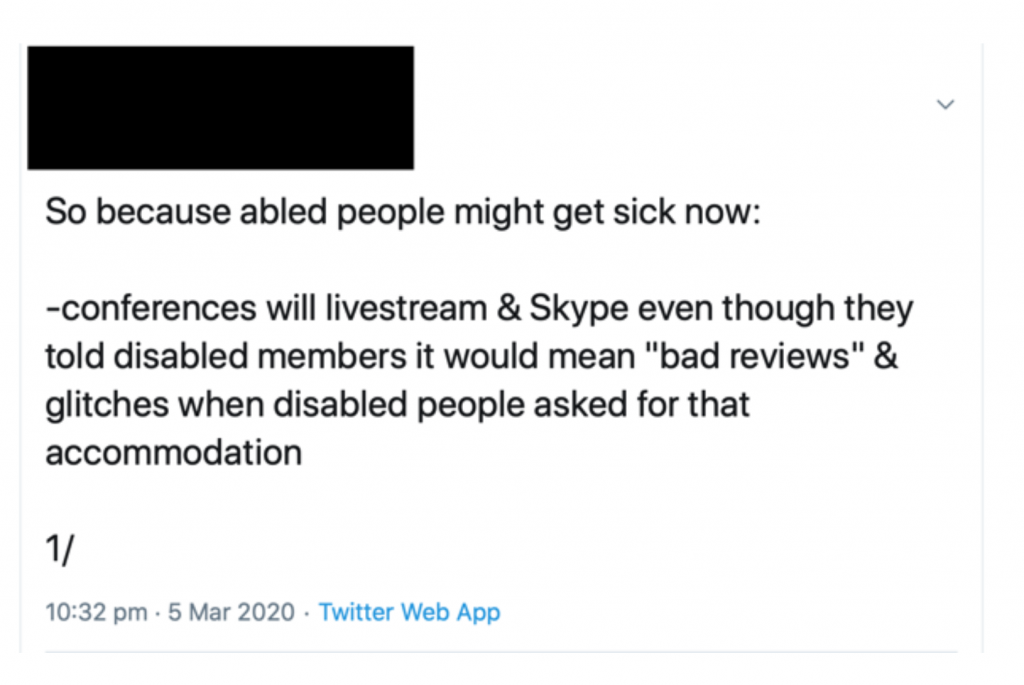

It might be tempting to point to the cancellation of conferences and reworking of seminars as a major consequence of COVID-19, and to consider how difficult it is to recreate opportunities for conversations and collaborations that tend to emerge from interaction outside of the formal conference room.

However, as disability activists and scholars with caring and familial responsibilities have pointed out, these issues are long-standing. It should be a matter of shame that it has taken a global pandemic to force able-bodied academics to think seriously about alternative ways of working, when this has been so long denied to colleagues unable to be physically present at large, and often distant, events.

Instead, a problem more directly caused by the pandemic is how COVID-19 has radically disrupted postgraduate and PhD research, and will potentially reduce the time available to undertake ongoing projects. At the time of writing, some funding bodies have so far shown a willingness to ensure no cost extensions in proportion to the disruption experienced, but considerable anxiety and uncertainty still exists, and the internal research leave and fixed contract arrangements of individual universities are being addressed idiosyncratically. The absence of a sector-wide response – of guaranteed secure employment at (or above) present levels of pay for casualised staff – has begun to generate political action under the banner of a Corona Contract. However, even if agreed, the personal circumstances of researchers change over time, and their capacity to undertake the same work may well be altered in the future. The knowledge produced will thus likely be substantively different as a result.

Similar analyses can be applied at the level of teaching. As was made clear at the Modern British Studies conference last August, history modules are already being shaped by the short fixed-term, zero-hour contracts spreading throughout academia. This has often reduced preparation time and opportunities for scholars to create their own offerings, leading to modules being inherited and reworked where possible by temporary staff. Individual universities have used COVID-19 as legitimation for laying off staff or refusing to continue contracts of fixed-term employees, and together with social distancing the landscape of teaching looks very different as a result.

*

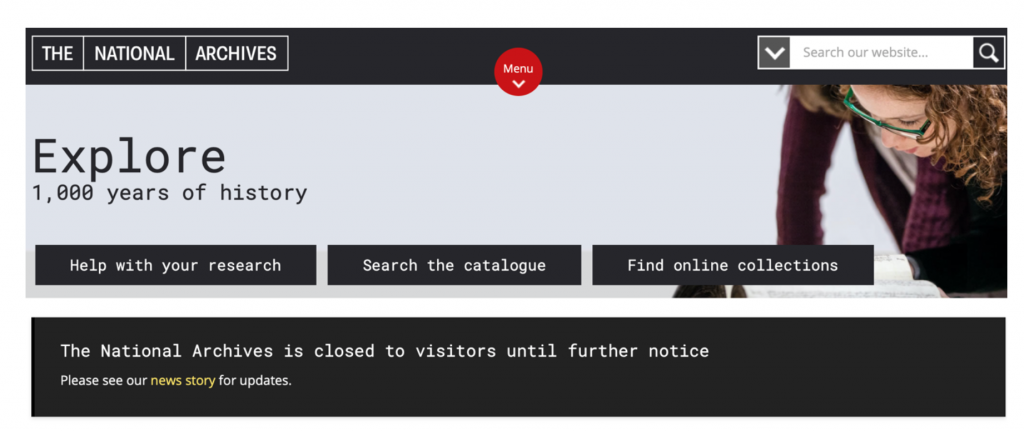

Of course, the pandemic is also shaping the knowledge it is possible to produce at the level of sources and methods.

Closures of archives and libraries has ensured a majority of resources remain inaccessible, and de facto quarantine is altering the way we can undertake oral historical work. (Given that the direction of an encounter is often shaped by the embodied interaction of interviewer and interviewee constructing the interview together in the same room, it is likely that even online interviewing will produce different testimonies.)

Some textual and visual materials are available online, partly due to digitisation and partly due to the increasing use of the internet as historical object and source.

However, a reliance on digital and virtual sources has its own implications for how we relate to, use, and think about historical materials.

For instance, texts that are available digitally and made keyword searchable can grow in epistemological importance. Equally, engagement with uncatalogued materials becomes impossible, and the assessment of a source’s materiality – its physical substance, potential sensory responses, clues to its production – are also precluded or made more difficult. In this sense the pandemic risks compounding historians’ existing reliance on the narrow range of sources that have managed to survive, and which have often been produced by social elites and from positions of (often violent) power. We will require further innovation in approaches and methodologies to avoid reproducing historical violence in the present.

At the same time, public and political discourses of healthcare, disease and contagion – as well as experiences of illness and practices of social distancing and self-isolation – are also altering how we might read and interpret our sources.

At a very basic level, I am currently revisiting my own work on waiting rooms. Under present conditions, materials relating to concern of infection are beginning to stand out more. References to feeling disturbed or diminished by waiting with patients with ‘hacking coughs’, for example, take on greater resonance, as do recollections of the way such anxieties shaped practices of attending surgery and sharing the time of waiting.

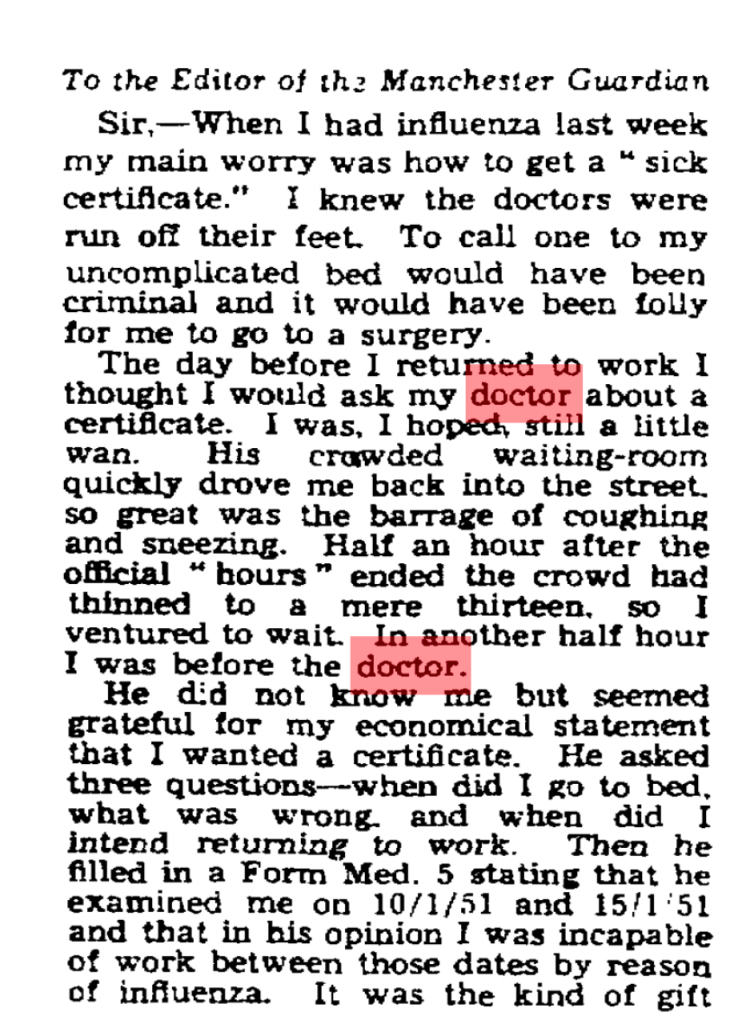

Take, for instance, one letter to the Manchester Guardian in 1951 about trying to collect a sickness certificate:

The day before I returned to work I thought I would ask my doctor about a certificate. I was, I hoped, still a little wan. His crowded waiting-room quickly drove me back into the street, so great was the barrage of coughing and sneezing. Half an hour after the official “hours” ended the crowd had thinned to a mere thirteen, so I ventured to wait. In another half an hour I was before the doctor.

Previously, I may have read this in terms of anxieties of waiting for – and consulting – the doctor when appearing healthy, in relation to the performativity of sickness. Equally, the source raises questions about the length of acceptable waiting, the responsibilities that doctors had to attend their patients after surgery hours, and the role of the medical profession in sick note certification. Even though I would have registered the disquiet with the waiting room as a source of infection, the fear of contagion would not have hit home in the same way.

Similar alterations in my interpretation have manifested in relation to GP’s frustrations with patients bringing in “dirt” to their waiting rooms. I have previously read such complaints in highly symbolic terms, in line with my interest in how discourses of dirt and cleanliness have been historically racialised and classed. Now, however, I am paying greater attention to dirt’s materiality. Though GPs’ irritations cannot be conceptually divorced from “dirt’s” cultural values, my own anxieties around the ongoing pandemic has made me appreciate the medical concern with hygiene embedded in GP’s choices of easy-to-clean materials for redecorating waiting in a period of regular infectious disease outbreaks.

Finally, even should the present proscriptions around “staying home” be eased, and libraries and archives swiftly reopen, the emotional experience of being in and using such spaces will also have been altered.

I already feel much more “exposed” simply going to a small supermarket, so I can only imagine that the experience of using public transport, sharing the space and time of research with others, and interacting with well-handled resources will be radically different for some time. To presume that such affective responses will not alter how I interact with historical sources (the time I can bear to be with them, how much more I rely on digitised versions) or the sorts of questions I will ask of them would be disingenuous.

*

There are, of course, much more complicated ways to think historically about epidemics, time and care in relation to scholars’ experiences of the present moment, and undoubtedly our teaching on history of disease and medicine modules will also be shaped by our students’ personal perspectives on their lockdown and social distancing.

Moreover, that I – and scholars like me – are only beginning to consider such questions seriously can itself be historicised.

This very reflection is the product of my having grown up in a period and place in which my privilege as a heterosexual, white (once working-, now solidly middle class) male living in Britain has afforded me protection – not simply from the epidemics that have tended to exist geographically and socially “elsewhere” (from HIV/AIDs to Ebola) but also from the structural violence that has consistently distributed disease disproportionately among the poorest and those most discriminated against in Britain (and globally). Even now, my positionality is proving protective, as underlined by reports that BAME communities are suffering disproportionate mortality from COVID-19.

Given the racial, class and gender disparities among the historical profession, I suspect that my experiences may be widely shared.

Nonetheless, whether explicitly discussed in acknowledgements, expressed within the subjects, questions and contours of research, reflected in how we organise and practice intellectual network formation, or manifest in the conditions within which teaching is delivered, the effects of COVID-19 on the present and future of historical scholarship will likely be widespread and significant. As such, though academic departments are by no means the only source of historical knowledge and narrative, it is fair to say that the present pandemic is also rewriting the past.

Notes

[1] For classics in the field and useful reviews: S. Shapin and S. Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air Pump: Hobbes, Boyle and the Experimental Life, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985); S. Woolgar and B. Latour, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); K. Knorr Cetina, Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge, (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1999); L. Daston and P. Galison, Objectivity, (New York: Zone Books, 2010).

[2] The most self-conscious example I have seen is the preface to a history on international development and the social sciences, which begins: ‘this book as much as the institutions which are its subject, comes out of a particular history, a certain intellectual climate, and specific funding possibilities’: R. M. Packard and F. Cooper (eds), International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), p. vii. For examples of texts firmly grounded in the historian’s own positionality: C. Hall, White, Male and Middle Class: Explorations in Feminism and History, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007 [1992]); C. Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives, (London: Virago, 1986).

[3] For instance: A. Green and K. Troup, The Houses of History: A Critical Reader in History and Theory, Second Edition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016); L. Jordanova, History in Practice, Third Edition, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019).

[4] E. H. Carr, What is History?, Second Edition (London: Penguin, 1990 [1961]), p. 30.