Whilst “wasting time”/“productively searching for historic pop culture representations of waiting” this week [delete as appropriate], I happened upon an episode of the sketch show, A Bit of Fry and Laurie from the early 1990s. In one of their “talking head” parodies, Hugh Laurie’s character comments:

“Well, we had our first child on the NHS. And had to wait nine months…

…Can you believe it?”

At the risk of proving E. B. White correct (and ‘killing the frog’), on the surface the joke played upon well-known durations of pregnancy, and invites us to laugh at the commentator’s ignorance.[i] The skit, however, also lampooned a certain type of caricatured middle class NHS user: one who approached health care with consumerist expectations, and who was prone to making (in this case, unreasonable) complaints about public service inefficiency.

The sketch, in other words, was a response to changing popular and parliamentary approaches to health care.[ii] As Sally Sheard and Alex Mold (respectively) have demonstrated, political and managerial attention to health service waiting undoubtedly intensified during the 1980s and early 1990s, and the period witnessed an individualisation of patient consumerism more generally.[iii]

Yet, as early Waiting Times research is showing (and as suggested by the ageing Laurie’s character), patient dissatisfaction with delays and waiting had been a feature of the NHS since its beginning.

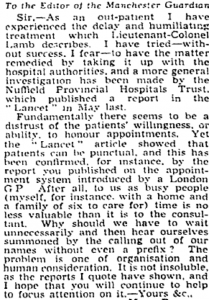

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, for instance, Britain’s newspapers carried numerous letters from patients discussing their experiences of waiting for consultations in general practice and hospital outpatients, as well as deploring the waiting lists for hospital appointments, admission, and treatments.

Patients attending for consultations described waiting as ‘irksome’, ‘inconvenien[t], and ‘endless’.

Most did not explain why they were displeased at this wasted, interminable time, perhaps assuming the reasons to be obvious. However, we can find glimpses.

Some correspondents hinted that frustration arose from misaligned public and private schedules. They had multiple personal and social responsibilities, and time became an economic resource: time spent waiting was time taken away from other tasks.[iv]

There were, however, more symbolic concerns. The prioritisation of medical time over the patient’s own was a source of irritation, especially when subsequent encounters were depersonalised.

Complainants often criticised the self-interestedness of doctors for appointment system failures and expressed dismay at clinicians for arriving late.

Yet, even when the doctors were considered courteous and blameless (with administrators were positioned as the villains of the piece), correspondents suggested that the squalor of public environments of waiting compounded their physical and psychological distress, and made their experiences almost unbearable.

Of course, early patient responses to waiting also varied.

As with newspapers and political parties, some letters linked their quotidian experiences to broader political points.[v]Letter writers and Mass Observation respondents both echoed public narratives that queues were either the inevitable result of iniquitous, incompetent socialism, or temporary, and signs of egalitarian health care extending to persons previously priced-out of access. Others were tentatively resigned to waiting simply being a part of mass medical practice.

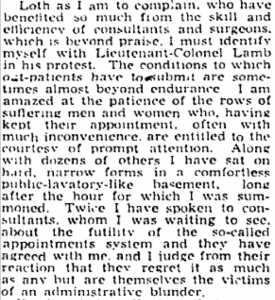

Yet, whether incensed or accepting (or simply mildly irritated), the vast majority of correspondents to publications and surveillance machinery, offered possible solutions.

Commentators suggested disaggregating appointments (rather than block booking everyone for the start of the clinic) and providing better information on the order of patients to be seen, as well as suggesting that waiting patients ‘equip themselves with a book or piece of knitting’ (‘it seems only common prudence’).[vi]

Like the Doctor looking for a fez, one correspondent seemingly got a little carried away in their endeavour, suggesting: ‘the waiting period should be made more pleasant by decorating the walls more attractively, better use of light, plenty of up-to-date magazines, books etc., flowers and pot plants, even an aquarium or small aviary, but most of all an air of cheerfulness and efficiency about the place.’[vii]

Although likely containing only the viewpoints of a very specific subset of the general population, these letters and survey responses thus offer considerable insight into waiting in the early NHS.

They shed light into the power dynamics at play in British medicine (for instance, whose time was prioritised). They highlight how modernist drives to “synchronise” individual, public, and institutional time had ordered the lives of mid-century patients and practitioners, but caused psychological distress when disturbed.[viii]

They also offer a glimpse into the longer history of quotidian experiences of waiting as slow and endless, and demonstrate the importance of comportment and environment to such perceptions.

Crucially for our appreciation of ‘80s and ‘90s sketch shows available on popular streaming services, however, they also underscore how political opposition to public services, and complaints about waiting in them, are as old as the services themselves.

Dr Martin Moore is the historian working on the Waiting Times project.

Notes

[i]White reportedly said: “humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind”. Those innards would likely be purchased by high-end restaurants and served on a bed of puréed dreams, now, however…

[ii]The show itself was well-known for lampooning older traditions of conservative morality, as well as what were then termed “Thatcherite” views of business and national services. It once suggested that Mrs Thatcher herself could be easily replaced by a coat hanger (to the nation’s benefit), and satirically created its own “Comedy Charter”, ‘a basket of top proposals’ to enable the viewer to complain and thus maintain the show’s quality and standards. The latter was a conscious play on the spate of such documents that followed John Major’s “Citizen’s Charter”, one of which was a “Patient’s Charter” that included minimum waiting times for patients.

[iii]S. Sheard, ‘Space, place and (waiting) time: reflections on health policy and politics’, Health Economics, Policy, and Law, (Early Access Online); A. Mold Making the Patient Consumer: Patient Organisations and Health Consumerism in Britain, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015).

[iv]G. Horobin and J. McIntosh, ‘Time, risk and routine in general practice’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 5:3, (1983), 312-31.

[v]J. Moran, ‘Queuing up in Post-War Britain’, Twentieth Century British History, 16:3, (2005), 283-305.

[vi]B. M. Fleming, ‘Hospital out-patients’, Manchester Guardian, 13thJanuary1953, p. 2.

[vii]H. Sumerfield, ‘Out-patients at hospital’, Manchester Guardian, 8thJanuary1953, p. 4.

[viii]B. Adam, Timewatch: The Social Analysis of Time, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995); Jacques Le Goff [translated by Arthur Goldhammer], Time, Work and Culture in the Middle Ages, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).