What the Papers Said: The NHS at 70 – Promises and Discontents

Martin Moore writes:

Earlier this year, the Waiting Times team collaborated with the Centre of Medical History and the Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health at the University of Exeter to run a public workshop to mark the 70 years of the NHS.

The aim was to use the intense interest in the service generated by the 70thanniversary to bring historical reflection on present day concerns.

The day encouraged discussion among the diverse participants, with exchange structured by three academic papers and provocations. The first, by Jonathan Barry (University of Exeter), provided insight into how the major broadsheet press treated the creation of the health service, whilst the second by Andrew Seaton (New York University), reflected on the everyday experiences of life on the wards of NHS hospitals. Among other things, these papers raised important points about the way that support from the press and middle-class users in particular was essential to securing the political future of the nascent service.

My own paper looked at the different ways that the politics of welfare and values attached to the NHS influenced patient perceptions of waiting for referrals and appointments in surgery and outpatient departments.

Of course, frustrations with waiting were often underpinned by agonising uncertainty, physical pain, and a more general anxiety about wasting time that might have been better used elsewhere.

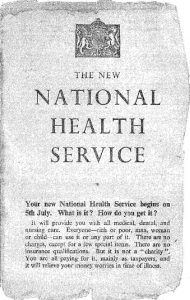

Nonetheless, the promises of – and discontents with – the values of the welfare state and universal health care structured interpretations of waiting. For instance, for some of the newly enfranchised, queuing for spectacles was seen as the result of the egalitarian return of the repressed. By contrast, for others, waiting in outpatients for hours was seen as a failure to fulfil promises to “universalise the best”, and forced people into the arms of private medicine.

The promise of speed in alternatives to the NHS (which is itself built on the exclusion of large-scale demand) is still an ever present in marketing campaigns for providers.

One issue I wanted to give particular emphasis in my discussion, however, was how the early NHS had failed to incorporate patient perspectives within its structures. The NHS was essentially created as a way to bring doctors and healthcare staff into state services and thus expand access to a comprehensive and equitable health service to all.

Yet, although grounded in socialist and social democratic traditions (among other influences), the creators of the service paid little attention to democratic input other than through the selection of governments over election cycles.

Patients and their families rarely had direct input into the design of services in the early years of the NHS, and there were no formal mechanisms for raising complaints or providing patient perspectives until after scandals in long stay hospitals in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

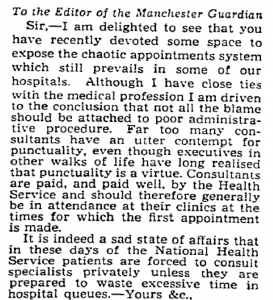

Prior to then, if patients were lucky complaints about waiting might be considered institutionally, but the few internal investigations I have seen all found “no case to answer”. In such circumstances, we can see patients’ letters to the press as arising out of frustrations having no alternative route for expression.

I wanted to outline this history at the event to raise questions around accountability and inclusion that exist outside the usual managerial frames of audits and surveys. I also wanted to ask participants on the day about how we might build the local components of the NHS as democratic institutions, incorporating patient expectations into services in a way that might escape the traps of “rights and responsibilities” discourses.

Asking these questions, I believe, might have some import for our contemporary understanding of waiting. If, as my paper suggested, our experience of waiting is intertwined, at least in part, with historically-specific ideas of what is owed, then perhaps our waiting might take on a different set of meanings if those who are waiting are a part of the promise-making process.

These themes, along with many others raised by the workshop participants, will form part of an ongoing discussion that we hope to have over the coming few years.

Dr Martin Moore is the historian working on the Waiting Times project.