MAKING THE MOST OF WAITING

Notes from the Waiting Time workshop held at the Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health, 12 June 2019

If time is a great healer, is waiting the problem?

Florence Nightingale (1859) certainly thought so. She saw it as bad for health – “apprehension, uncertainty, waiting (my italics), fear of surprise…do a patient more harm than any exertion.” It’s tiresome too, as the Kinks noted in 1965 and in the meantime, we’re all Waiting for Godot (who never comes). For health systems, waiting is a mark of inefficiency that undermines ‘customer’ confidence. It is a focus for targets and management expedients in a culture which expects action, now!

But, is this the whole story?

Earlier this summer, a workshop at Exeter showed that – sometimes – embracing the wait can be its own reward. It’s the quality of care and use of the time spent waiting that makes the difference between a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ wait. It was a reminder that, sometimes, ‘wait and see’ is a plausible alternative to immediate action when treatments and outcomes are uncertain.

A long wait can allow health issues to resolve through natural healing. Rest and recovery may produce a better outcome than immediate surgery. But, waiting can also mean delay, with later diagnosis and treatment and even earlier death if serious conditions are not caught in time. The challenge – as ever – is to determine priorities from among competing needs. For example, handlers seeking to make the right call on waits for ambulances face an acute dilemma balancing availability of transport with urgency, system rules and patient need.

Waiting allows for exploration and for time to assess progress. ‘Watchful waiting’ at gender identify clinics allow young people to grow while services explore and assess their development. Such exploration can, however, mean suffering for young people clear in their desire to transition, not least by allowing the physical developments that will make the eventual transition harder. Parents and carers are not always persuadable about the merits of such delay and may be suspicious of delays in accessing scarce services. The right words can help. ‘Active monitoring’ seems to work better than ‘watchful waiting’.

Waiting – not always so bad?

Waiting can also support the therapeutic process. It can validate individual experience as the end of life approaches, affirming the value of lives lived for individuals and their families. Creative expression and appreciation through poetry, music, painting (van Gogh’s “Starry Night” was given as a stunning example) and nature can provide a vehicle for this approach. Importantly, it reminds people that they are not just “boring old farts”, as one participant in the Waiting Times’ hospice project remarked.

The policy challenge is to acknowledge – and balance – the positive aspects of waiting with the negative aspects of delay in care and treatment. This challenge will be met by better understanding the social and cultural context of such care, by harnessing patient experience – including meeting concerns about being fobbed off because of a lack of – or cuts in – available services, and reflecting these concerns in the design and delivery of services that are welcoming and available to all.

Developing services that reflect the positive aspects of waiting will require:

- changing the character of public services by putting the individual at the heart of service provision, and through greater transparency and dialogue about the options for care and treatment;

- being straight about the role that access to services – or lack of it – plays in creating harmful delays and widening health inequalities; and

- restoring the care and support of individuals to a central place in the work and training of professionals, and allowing sufficient time in day-to-day routines to ensure a good quality of care.

This will not be easy.

The Centre’s DeStress project has shown how stigma and deterrence have re-entered the public service lexicon affecting its character, and citizens’ experience. Vulnerable and disadvantaged people bruised by claiming welfare benefits fear this ‘hostile environment’ will seep into the health service, notwithstanding the efforts of the NHS to resist it. It can take time to build courage to visit the GP and while waiting at the surgery, people feel anxious, doubtful they should be there, and guilty about wasting the doctor’s time when services are under strain. This is a recipe for an unsatisfying consultation. A rapid reach for the prescription pad can only reinforce patient doubts and wider sense of powerlessness, which – in turn – acts as a barrier to further engagement and greater risk of ill-health

Timely access to services will help maintain good health and prevent disease but this is difficult to achieve with big differences in service provision – and waiting times – across the country. The ‘inverse care law’ – where the availability of good medical or social care tends to vary inversely with the needs of the population served – is alive and well.

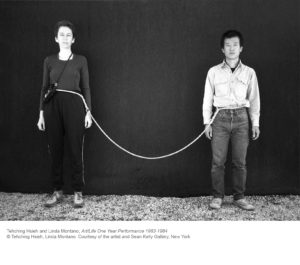

While there is no ‘one size fits all’ formula for waiting – patient need and the training and capacity of professionals vary – the workshop heard that professionals holding hands across a ‘shark infested sea of uncertainty, diagnosis and treatment to an island of recovery or resolution’ can maintain the dignity, mental health and wellbeing of individual patients during this journey. Yet, social workers and others are not always able to sustain this caring role, given today’s emphasis on management organisation and cost concerns. Volunteers often have to fill the gap. There is a poor fit too between family needs and the organisation of primary care, and a lack of clarity about available support services.

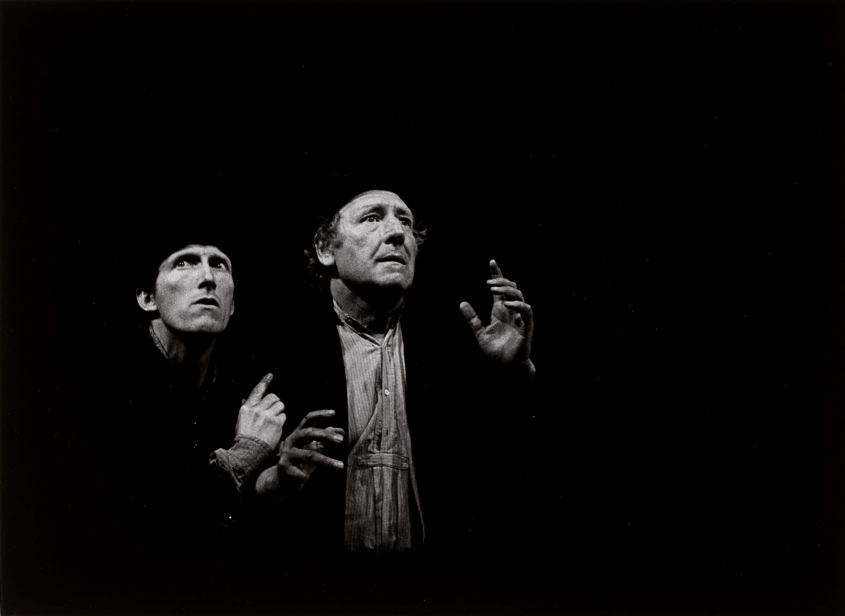

“Don’t forget,” said Florence, “patients are shy of asking,” and without explanations they remain in ignorance about why they are waiting. A situation where ‘nothing happens, nobody comes and nobody goes’ is disorientating. It also reflects professional uncertainty and a lack of confidence in the system. Everyone wants health services that are delivered in a fair, timely and appropriate way. However, better waiting list management will not deliver this on its own without a clear focus on the quality and time taken over the care and treatment of individual patients, and the views and experiences of patients themselves.

This blog was written by Dr Ray Earwicker, honorary fellow, Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health, University of Exeter