‘My own doctor is a charming man when one can eventually win an appointment to see him’: accessing the GP and the time of care in British general practice

Martin Moore writes:

At a meeting of English local medical committees during November last year, GPs passed a motion to end home visits as a contractual obligation for NHS practitioners, advocating for a special acute service to be established to undertake such work.

Although, according to recent NHS data, on average only 1% of total primary care appointments were for home visits, the motion provoked a considerable backlash among patient groups, senior healthcare professionals, the press and Government ministers.

Critics broadly focused on the capacity for severely ill and immobile patients to access the GP, whereas supporters argued that GPs ‘no longer have the capacity to offer’ visits. At its heart, in other words, were questions about for whom and for what GPs should reasonably make time.

As my recent work on appointments systems is revealing, GPs’ time and patients’ rights of access to care have formed a central object in public debate since the foundation of the NHS. By contrast to the current proposals, however, the emergence of full-time appointments systems for surgery sessions in general practice generated far less initial resistance, despite affecting a far greater proportion of the practice population.

‘Much of the overwork of which doctors complain is due to lack of proper business methods’

The first decades of the NHS witnessed a considerable change in how people waited for a GP consultation.

In the early 1950s, only 2% of British general practices employed full time appointments systems for their surgery sessions.[1] In the vast majority of practices, those patients wishing to see the doctor could simply arrive at the premises during surgery hours and wait to be seen in turn. Even practices with appointments systems quietly reserved part of the surgery session for patients arriving without an appointment.

Finally, for those too ill to come to the surgery, visits were common; around a quarter of consultations on average occurred in patients’ homes.[2]

By the early 1970s this situation had dramatically altered. Around 80% of practices now employed full-time appointments systems.[3] Crucially, changes to NHS rules empowered doctors to defer treating patients who they felt were not in need of immediate attention. Patients were thus increasingly unable to access the doctor on demand without an appointment. A wait for the doctor might stretch to several days if one was unavailable immediately.

As with contemporary discussion around home visits, GPs’ concern with time pressure generated interest in appointments systems. Following the creation of the NHS, many GPs bemoaned having ‘much more work’ and feeling like they were ‘chasing [their] practice downhill all the time with no hope at present of ever catching up’.[4] As a result, many doctors sought organisational innovation to achieve ‘more economic use of … time and energy’.[5]

Notably, one particular attraction of new systems was that they might ‘reduce the demand for visits’, as reduced crowding and waiting times could make surgery attendance less taxing.[6] The time saved by reduced travelling could be put to use elsewhere.

Efficiency was not the sole factor motivating GPs to take up appointments systems, however. Traditional arrangements, for instance, could lead to late-running surgeries – any patient who arrived before doors closed had a right to be seen. As one satirical novel put it: ‘the patients came steadily to my cubby-hole, though every time I began to think about lunch and peeped outside there seemed to be as many waiting as ever’.[7]

Constant work and anxiety about the waiting room’s ‘vast unknown population’[8] left GPs feeling exhausted and stressed. ‘A life of uncertainty as regards the working events of a day’, one GP noted, ‘is nervously exhausting at all times’. Only with an appointments system was ‘the element of being in a hurry… eliminated’ and ‘a much calmer atmosphere’ established.[9]

Appointments thus enabled GPs to reduce daily physical and psychological strains, and offered greater control of time in their working and social life. They could now make time for dinners and professional development opportunities. Such pursuits also led enterprising practitioners to engage in the first out-of-hours companies and develop rotas for the burden of night calls.[10]

‘They are not just “the next patient, please”’

Such substantive change did not go unnoticed. Traditional GPs in particular expressed concerns about how appointments created psychological barriers to attendance for patients with uncertain symptoms, preventing the opportunity for early diagnosis.

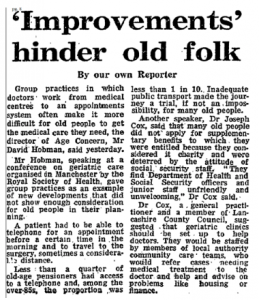

GPs also noted inequitable social consequences, pointing to poorer and elderly patients having difficulties making appointments. ‘The 3d for the telephone’, suggested one practitioner, was ‘an added expense to their budget’, whilst making timely journeys was made more challenging by reliance on public transport and greater geographical isolation.[11]

Generally, however, patients seemed to accept new systems during the 1960s. Consumer bodies lobbied for them, and surveys revealed approval ratings as high as 98%. Primarily, patients appreciated reduced surgery waits (on average being halved) and liked being able to integrate appointments into their day, ‘shopping in what would previously have been waiting time in surgery’.[12]

Doctors also noted that patients appreciated having protected time with the GP. They even suggested that the work involved in securing a consultation meant had a ‘better understanding of the value of the time spent in consultation… emphasis[ing] the importance of the doctor’s advice’.[13]

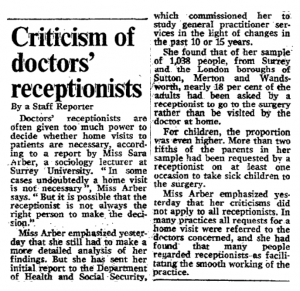

It was when appointments proved hard to come by that dissatisfaction manifested. In response, some patients lamented losing the traditional guarantee of same-day consultation, describing the queue as ‘much more humane’ than the delay and ministrations of ‘a dragon of a receptionist’.[14] Indeed, receptionists attracted considerable public ire.

By contrast, some critics noted the changing experience of waiting, bemoaning declining ‘comraderie’ in the waiting room.[15] Whereas once waiting patients were collectively left out of sync with the rest of the social and economic community – to paraphrase Harold Schweizer – under appointments they were out of sync with one another.

*

By the time appointments systems nationally began to struggle, reverting to older temporal orders was almost inconceivable. Individual practices did abandon appointments after bad experiences, but generally too much financial, organisational and psychological investment had already been made.

Today, receptionists are still maligned and the ‘same-day appointment’ has become an important metric for the NHS. Newspapers have even offered advice for getting an appointment for the day you want.

The drive for choice and immediacy in appointments has undoubtedly pressurised GPs to be time conscious, and – as in the 1960s – has contributed to the undesirability of home visiting.

Though drawing lessons from the past is a dangerous activity, given the historical drift away from home visiting – and present pressures to access GPs on demand – it wouldn’t be a surprise to see home visiting hived off from GPs in the near future.

If it were, reintroducing home visiting to GPs after the act may well prove as difficult as removing the appointment. The other consequences of this change, though, are far more difficult to predict.

Notes

[1] S. Hadfield, ‘A field survey of general practice, 1951-2’, BMJ, 2:4838, (1953), p. 701.

[2] N. Bosanquet and C. Salisbury, ‘The practice’ in I. Loudon, J. Horder and C. Webster, General Practice under the National Health Service, 1948-1997, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 47.

[3] ‘14 days to see your doctor’, The Lancet, 301:7809, (1973), 923.

[4] E. Anthony, ‘The GP at the Crossroads’, BMJ, 1:4661, (1950), p. 1078.

[5] J. Stevenson, ‘Appointment systems in general practice: do patients like them, and how do they affected work load?’, BMJ, 2:5512, (1966), p. 516.

[6] Central Health Services Council Standing Medical Advisory Committee, The Field Work of the Family Doctor, (London: HMSO, 1963), p. 15.

[7] R. Gordon, Doctor at Large, (London, Michael Joseph, 1955)

[8] ‘Why are we waiting?’, Platform, (Basingstoke Consumer Group, October 1964), p. 28.

[9] H. N. Levitt, ‘An appointment system in a single-handed general practice’, The Practitioner, 185 (1960), p. 213.

[10] Bosanquet and Salisbury, ‘The practice’, pp. 58-9.

[11] N. C. Horne, ‘An appointment system for use in general practice’, BMJ, (Supplement, 29 November 1952), p. 210.

[12] D. Dean, I. M. Dean, B. R. Wilkinson, and R. McMurdo, ‘Appointment systems in general practice’, BMJ, 1:5434, (1965), 592. Also: J. M. Bevan and G. J. Draper, Appointment Systems in General Practice, (Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, 1968), pp. 113-15

[13] The Field Work of the Family Doctor, p. 27.

[14] K. Johnstone, ‘Trying your patients’, The Guardian, 1 February 1979, 13.

[15] J. Cunningham, ‘Doctors avoid ‘unnecessary’ calls’, The Guardian, 2 May 1973, 7.