In this long read, Martin Moore shares thoughts from his research into how British GPs have historically configured time in relation to “the consultation”.

*

Towards the end of her pregnancy in the summer of last year, my partner suffered a severe bout of iron-deficiency anaemia. Her antenatal care had been rather disjointed through the impact of the pandemic, and it turned out that she had gone several weeks without treatment. Anxious and exhausted, she called the local GP surgery and awaited a telephone consultation with an available doctor. Given the issues we had experienced co-ordinating care in the preceding weeks and months, we did not wait with great expectations.

Figure 1 – Me, thinking of this GIF-based joke

The call came, typically, in the middle of one of her work meetings that day. The doctor asked how she was feeling, reviewed her record and talked us through the treatment options.

Once the prescribing was done, however, the doctor kept the call – or rather, the consultation – open. They asked how things had been, whether we had any worries about the upcoming labour. They were happy to chat and listen, acting in clear violation of the “one appointment, one problem” posters that had covered the walls of the physical waiting rooms we were now locked out of.

Figure 2 – If only the poster was clearer about how patients should bring their problems to the GP

This unexpected offer of time and attention – of care in a period when previous promises of care had been thrown into disarray – was unexpectedly moving, valued as much as the iron tablets that followed.[i]

*

At least in its early months, the pandemic had complex effects on general practice consultations.

However, one particularly notable shift was a sharp fall in the number of appointments being made.

Whether resulting from anxieties around infection, from practice policies, or perhaps from political appeals for the public to wait with problems – to refrain from engaging services where possible in order to “save our NHS” – a year-on-year comparison between May 2019 (24.6 million appointments) and May 2020 (16.6 million appointments) revealed a 30% decrease.

GPs experienced – and displayed – mixed feelings to this development.

On the one hand, there were fears that patients would suffer consequences. For instance, that early signs of cancer would be missed, reducing or missing the temporal window in which investigation and treatment would be most effective. These certainly appear to have been borne out in terms of referral figures.

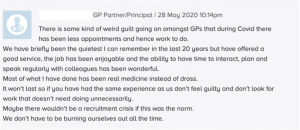

On the other, some revelled in the time that had seemingly been created by reduced demand, and even suggested that the “dross” work that they usually performed had decreased.

Figure 3 – Comment to “Pulse” (Magazine for GPs)

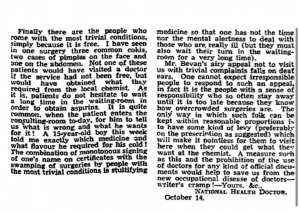

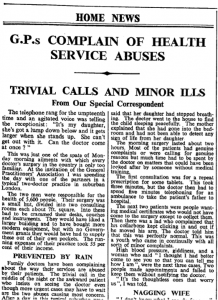

Such complaints about trivial and minor illness – about not doing “real medicine” – are at least as old as the NHS itself.

Whether complaining about increased responsibilities for sick notes, “neurotics”, patients attending for conditions requiring no treatment (or treatment they could, and previously would, have performed themselves), or patients simply coming out of newly-formed “habit”, GPs had long pointed the finger at unnecessary demands as a cause of stressful time-compression. Worse, it supposedly took time and attention away from those who truly needed it.

Figure 4 – Manchester Guardian, 1949

They even labelled this type of attendance an “abuse” of the service, calling for ways to discipline patients for their behaviour.

Figure 5 – The Guardian, c. 1956

.

.

Figure 6 – The Times, c. 1964

*

Such complaints, were not, however, universal.

Particularly from the later 1950s and 1960s onwards, a minority of GPs rejected complaints around trivia. They noted that patients just “dropping in”, even with issues which might appear minor, provided useful opportunities for curtailing problems before they became serious.

Figure 7 – British Medical Journal, c. 1965

Others suggested that chronic attendance – especially for minor ailments – was actually a sign of unresolved conflict and trauma in a patient’s life. These were precisely the patients who needed time and attention, both to ease their suffering and to eventually end their regular attendance at the surgery.

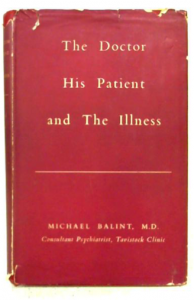

This was particularly the case for those doctors associated with the work of the psychoanalysts Michael and Enid Balint. Together with colleagues at the Tavistock Clinic in London, the Balints ran regular “research seminars” through which local GPs could discuss cases and the psychosocial features of general practice.

Out of this work came a conviction that the most potent drug a GP could prescribe was the doctor, but only if prescribed in the right way and in the right amounts.

Starting from the belief that many seemingly physical illnesses and symptoms were in fact psychosomatic – rooted in how present-day social, emotional and mental conflict triggered past traumas and developmental problems – the Balintian model of the consultation reframed the temporal aspects of the doctor-patient encounter.

Firstly, the consultation connected past, present and future in new ways.[ii] Patients’ recurrent attendances were pathologized as psychological repetitions that required exploring both present relationships and early childhood.

In his foundational 1957 report on the GP seminars, The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness, Michael Balint even hypothesised the existence of a “basic fault” within every individual, emerging out of the ‘considerable discrepancy between the needs of the individual in his early formative years (or possibly months) and the care and nursing available at the relevant times’. This fault, he suggested, potentially structured ‘all the pathological states of later years’ (pp. 255-6).

Figure 8 – What’s internationally renowned and red all over?

Equally, the GP’s own routines were cast as having contributed to recurrent physical symptoms and consultations with the patient – typical practices of clinical examinations reinforced the sense that patients should only bring physical complaints to the doctor, whilst uncritical reassurance that “nothing was wrong” failed to address ‘the patient’s most burning demand for a name for his illness’ (p. 25). Instead, ‘the patient’s increasing anxiety and despair’ could result ‘in more and more fervently clamouring demands for help’ (p. 26)

Secondly, during the 1950s, proponents of this psychoanalytically-informed practice promoted the wider adoption of both hour-long interviews to explore the potential psychosocial causes of illness, and regular follow-up consultations to undertake psychotherapeutic treatment.

Balint warned GPs, however, not to rush such interactions, but instead to travel at the patient’s own pace.

‘It is equally dangerous to hurry a patient, not to allow him sufficient time to work out his own solution of the problem and to overcome his resistances to it, especially those caused by shame, embarrassment, and above all, by guilt feelings. All this needs tact, patience and time’ (p. 275-6).

Finally, within this framework of care, consultations with the patient were neither considered as one-off events nor considered as a chain within a single ‘episode’ of illness.

Rather, they formed important parts of an ongoing and continuous relationship between practitioner and patient. Through repeated encounters, the GP and patient would not only get to know one another but develop a mutual trust and respect.

It was this mutual investment, moreover, that provided GPs with a particular opportunity to undertake psychotherapy. It allowed the GP to undertake both ‘considered risks’, and to be patient and watchful.

‘Even if the openly psychotherapeutic relationship is broken off’, Balint suggested, ‘the patient may, and indeed does, come back to his doctor with a cold, or indigestion, or a whitlow, or a bruised finger, or to have his child inoculated, and so on ad infinitum’ (p. 158).

Indeed, he went on:

‘If for some reason or other the progress of treatment has become blocked, and further probing is either unsuccessful or inadvisable for the time being, a well-calculated amount of medicine will bring the patient back at a time when the atmosphere may be more favourable. Again, if the practitioner is uncertain whether the time has come to stop, arranging for the patient to come back for a new prescription, or a check-up enables him to keep an eye on developments and to “start” again if events demand or suggest it’ (p. 170).

The temporal orders constructed, the offer of time made, and the type of attention afforded to patients within the psychosocial general practice consultation thus entailed a considerable reworking of more clinically-oriented practice.

*

As Shaul Bar-Haim has noted, this psychosocial orientation to general practice, emerged at a time when the morale and status of general practice was at a nadir, and some GPs saw within it an opportunity for remaking their identity and positionality within British medicine.

It greatly influenced many of the doctors who assumed leading roles in academic general practice, and particularly the Royal College of General Practitioners, into the 1960s and 1970s. The lasting legacy of the Balints, moreover, can be seen in the continuation of the Balint Society to the present day.

However, the effect on everyday practice appears to have been neither immediate nor widespread.

Academic general practice was only slowly constituted over the early post-war decades, and vocational training not made a compulsory part of qualifying for general practice until the 1980s.

Moreover, elite institutions of general practice could be hostile and exclusionary spaces. As Julian Simpson’s work suggests, many South Asian practitioners – on whom the NHS had come to rely heavily, particularly in unfavoured industrial and urban settings – experienced racism and discriminatory attitudes in elite organisations, freezing out large swathes of the GP workforce into the 1980s.

At the same time, although GPs’ feelings of time-compression reflected shifting working conditions, their autonomous choices about temporal patterns of work, and changing cultural expectations around medical practice, they also emerged from doctors’ engagement with patients’ chronic and unresolvable demand for GPs’ attention.

Of course, individual consultations could be extended relative to the problems being discussed. Likewise, research into GPs’ working days (weeks and years) consistently found variation in the average duration of consultations. Whereas some practitioners in the 1950s reported average consultation times of 5 minutes, others recorded figures of 8 and a half minutes.[iii] Similar variations were recorded in subsequent decades.[iv]

Largely, these were the products of GP’s own ingrained habits. However, there were some structural limits to such variations.

Though studies found that only very small or extremely large patient lists exerted pronounced effects on the average duration of consultations, or on the number of consultations that GPs conducted per week, this same work also suggested that larger list sizes were not consonant with high annual consultation rates. They thus amounted to less time given per patient over the year.[v]

In other words, at some point, the time offered to one patient either needed to be compensated for by shortening consultations with another, or by seeing some patients (or even the same patient) fewer times over the year.

To refer back to the discussion of “trivia” or “dross”, then, GPs’ complaints here undoubtedly reflected culturally-bound determinations of who “deserved” attention. Nonetheless, they also reflected the structures within which general practice has had to work.

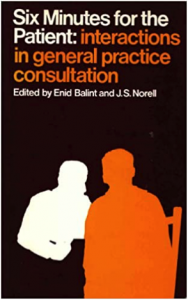

Indeed, even doctors influenced by Balint admitted that compromises to pragmatism were required; they developed new “flash” techniques for psychotherapeutic work over the 1960s, publishing their research in a text tellingly titled Six Minutes for the Patient (1971).

Figure 9 – Has there been a more 70s book cover?

These structural constraints were, to be sure, mutable to some extent.

Appointments systems enabled the GP to regulate the number of patients consulting per surgery session. Likewise, professional bodies lobbied government around payments and list size limits to make smaller list sizes practical propositions.

And indeed, drives to offer greater time to patients were not unidirectional. The Royal College adopted an ideal of the 10-minute appointment in the 1980s, and this still provides the standard time allotted to patients today.

Figure 10 – Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, c. 1989

However, should my reaction (and that of my partner) to our GP’s unexpected offer of time indicate anything, it is how trained we have become to expect this 10 minutes to be focused – and even pressured – ending with the (metaphorical or literal) tearing of the prescription pad, rather than being open ended.

*

It is likely that “our” GP’s generosity with their time reflected how their own consultation style found expression amid the shifts in working patterns experienced at that point in the pandemic.

Reports on video and telephone consultations from that period, for instance, demonstrated that they were, on average, shorter than in-person equivalents.

Moreover, our capacity to access tele- and digital medicine reflected our own racial, class and linguistic privileges: historical and contemporary research has shown that moves to new platforms have reinforced inequalities of access.

Our experience suggests, in this sense, that though the long-term effects of the pandemic on general practice are still in the balance, we must continue to be mindful of how formal changes in policy will not play out equally. Who receives time and attention will continue to be shaped by historical structures of privilege and discrimination, by long-formed expectations of what time is reasonable, and by practitioners’ own orientations to care in the consultation.

Martin D. Moore

Notes

[i] Thankfully, everything went as well as could be expected with the rest of the pregnancy and labour. We are now the parents of an adorable, disturbingly loud, 5-month old.

[ii] As Rhodri Hayward has shown, psychological and psychoanalytic concepts, perspectives and practices were not entirely new to British general practice: R. Hayward, The Transformation of the Psyche in British Primary Care, 1870-1970, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014) However, they were not particularly widespread by the mid-century, and Balint problematised GPs’ routines and patients’ recurrent appearances in novel ways.

[iii] Cf: John Fry, ‘A year of general practice: a study in morbidity’, British Medical Journal, 2:4778 (2 August, 1952), 249-52; Alistair Mair and George Mair, ‘Facts of importance to the organization of a National Health Service from a five-year study of a general practice’, British Medical Journal, (Supplement, 20 June 1959), 281-4.

[iv] T. S. Eimerl and R. J. C. Pearson, ‘Working-time in general practice. How general practitioners use their time’, British Medical Journal, 2:5529 (24 December, 1966), 1549-54; Norma V. Raynes and Victoria Cairns, ‘Factors contributing to the length of general practice consultations’, Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 30:217 (August, 1980), 496-8.

[v] D. Wilkin and D. H. H. Metcalfe, ‘List size and patient contact in general medical practice’, British Medical Journal, 289:6457 (1 December 1984), 1501-5.