When: Tuesday, October 22, 2019, 8:00 – 10:00 pm

Where: New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute, 247 East 82nd Street, NYC (btwn 2nd and 3rd Aves)

Register HERE, visit nypsi.org or call 212.879.6900 (New York, USA)

When: Tuesday, October 22, 2019, 8:00 – 10:00 pm

Where: New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute, 247 East 82nd Street, NYC (btwn 2nd and 3rd Aves)

Register HERE, visit nypsi.org or call 212.879.6900 (New York, USA)

Martin Moore reports from the field …

The European Association for the History of Medicine and Health held its biennial conference in Birmingham on August 27-30th, an event at which both Michael J Flexer and I were lucky enough to speak. Under the theme of “sense and nonsense”, the conference brought together scholars from around the globe to explore the emerging field of sensory history, covering topics as diverse as smell and health in the art of the Dutch Golden Age to the introduction of cocaine into China at the turn of the twentieth century.

The first paper from the Waiting Times’ team came on the morning of Thursday 29th from Michael, as part of the Senses and Modern Health/Care Environments network led by Dr Victoria Bates. As usual, Michael’s paper was a tour de forceof wit and insight, and generated some of the more interesting summaries on the Twitter once divorced from context…

Michael’s exploration of the semiotics of contemporary general practice waiting rooms provoked lively discussion, not least around how such spaces were reworked by contemporary political economies and moments of resistance to intended use.

However, two aspects of the paper stuck out for me.

The first was the way in which Michael deconstructed the concept of “sense” through Deleuze, pointing out that many individual aspects of the waiting rooms had anticipated user needs but generally failed to come together cohesively to make sense as a whole. The accumulation of relics (defunct signs of varied sizes, old magazines), unintentional juxtapositions (advertising social care for the elderly on a space reserved for infant welfare concerns), and perhaps even interrupted efforts to “dress” the space created a sense of incoherence, taking patients out of the “now” and scattering them throughout time (and space).

The second was the total absence of the general practitioner from the waiting room.

Responding to a question drawing on contrast with the premises of German GPs, Michael noted that these spaces almost consciously removed the doctor’s personality. In many respects, this absence emerged from contemporary structures of ownership, where GPs likely work in – rather than own – the spaces in which they practice. Indeed, this divorce created situations where doctors could not explain the presence of certain leaflets in their waiting rooms, nor could practice managers. Agreements were made to advertise certain products or services at the Commissioning Group level, and so the spaces of waiting would be subject to reshaping at the level of management rather than labour.

Both these points caused me to reflect on my own work, and on the specific history of general practice care in Britain.

My paper (delivered on the Thursday afternoon) looked to explore why GPs began to pay so much attention to their waiting rooms during the 1950s and 1960s, and how the changes being pioneered at this time reworked the sociality and sensory experience of waiting for primary healthcare. In this I began to consider some of the unintended consequences of certain changes, such as the use of public information notices, and here historical echoes with Michael’s considerations emerged. (For instance, how posters demanding patients be responsible for managing one’s own time, as well as that of the doctors, could ironically create a sense of disempowerment and distance from moments of care.)

It also deployed some rather cheap tricks to keep the audience interested…

However, what Michael’s paper made me appreciate were the ways in which structures of ownership could influence how waiting was shaped and experienced. Although the creation of the NHS removed formal “ownership” from GPs in that practices could no longer be bought or sold as private property, GPs nonetheless controlled how their practices were laid out and interiors designed. At least in the 1950s and 1960s, GPs largely determined how the time of waiting was passed – what patients were exposed to, and how they were held.

Of course, patients found ways to disrupt the best plans of doctors, such as damaging furnishings or removing materials from the premises, whilst the chatter that might pervade waiting rooms could hardly be legislated for or controlled if patients were determined. (Indeed, based on Michael’s observations, waiting in general practice may well have been more communal in the post-war decades, reflecting changing lengths of waiting, the number of patients in the waiting room and broader cultural practices of waiting in public spaces.)

Moreover, Michael’s references to how a space could be made “nonsensical” by the sediment of previous layouts or interrupted actions also underlined how I may have previously placed too much emphasis on the coherence of GPs’ plans for redecoration; in situ, and longitudinally, their decisions may have made less sense than intended.

Nonetheless, the contrast between our papers drove home how the aggregation of practice organisation since the 1990s, and particularly the 2000s, may well have altered the waiting experience for patients.

Beyond our panels, there were several personal highlights from the event.

The panel on “Modern Medical Visions” featuring Beatriz Pichel, Kat Rawling, and Harriet Palfreyman offered eye-opening (apologies for the pun) explorations of the way that photographs and drawings provided multiple modes of viewing patients and illnesses throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and underlined how such materials functioned in multi-sensory and experimental ways.

It also featured original artwork (can you guess which one is the creation of a medical artist?):

Claire Hickman’s discussion of birds and the therapeutic hospital environment was another paper that made me think about temporalities in new ways, and particularly the affective and psychological relations produced by asynchronous life-spans. (Although the absence of a “late parrot” was disappointing.)

However, perhaps the most invigorating – and humbling – paper came from Tracey Loughran’s keynote, which explored gendered and embodied time through women’s memories and experiences of menstruation.

The paper stressed the importance of historicising the body, placing it in shifting cultural and social contexts, whilst also not denying the embodied-ness of historical subjects. It thus raised important questions about how we might think about the ways that changing expertise and technologies around reproduction, conception and menstrual cycles have mediated women’s experiences of embodied time, establishing different norms, expectations, and practices across generations.

In addition, though, Loughran also queried the multiple temporal entanglements of doing historical research, and she ended her keynote reflecting on the embodied experience of being a female historian. She castigated those male academics who wasted their female colleagues’ time with self-indulgent – and ignorant – “more of a comment than a question” interventions, and who often took the same approach in everyday working life. She also called for female academics to resist pressures to take up less time and space, and to remind them that they were the future.

It was a powerful clarion call, and one which will definitely live long in the memory.

All in all, then, the conference was a fantastic – if somewhat exhausting – four days. It was intellectually enriching and raised politically vital issues. The University of Birmingham provided a great venue for the event, and my generous local guides made me appreciate the city much more than I had previously.

My only regret was that I was unable to attend every panel, with many running simultaneously. Well, that and the fact that there was no karaoke. Fittingly, I suppose my wait to sing “Time After Time” goes on …

Our research fellow Raluca will be talking at this day long event celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Balint Society.

The event will be at the Wellcome Collection, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE on Friday, 17 May.

The day will include the 23rd Michael Balint Memorial Lecture, speaker Peter Toon.

For more info and to book tickets, visit the Balint Society website.

Part One: Trauma and the Confusion of Tongues

10.00-17.00

2 June 2019

Part Two: The Psychic Life of Fragments. On Psychic Splitting

10.00-17.00

7 July 2019

Our research fellow Raluca will be running these two one-day courses on the work of Ferenczi at the Freud Museum in London at the start of the summer.

For more information, visit the Freud Museum page for Trauma and the Confusion of Tongues or The Psychic Life of Fragments.

To book for the courses, click on the images below.

The Psychosocial – Reflections and Developments

The Association of Psychosocial Studies ‘Reading’ Conference

Birkbeck, University of London

16 – 17 May, 2019

The Waiting Times team will be contributing to this two-day conference exploring the development of the psychosocial field of studies.

The conference will have reading sessions in the morning, with groups of no more than 20 participants. In the afternoon, delegates will come together in larger groups for discussion workshops.

For full details of the programme for the two days, including a complete list of the reading sessions, and to book tickets, please visit the conference Eventbrite page.

We’ll be taking part in the afternoon workshops on 17 May. Hope to see you there.

Our PI Lisa Baraitser is presenting at this international conference at the University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht on 7 May, 2019.

The conference – the third organised by the Concerning Maternity network – explores the lived experience of pregnant and maternal subjectivity. It will bring together writers, mothers, midwives, and academics in midwifery theory, philosophy, care-ethics, and psychosocial theory.

For more information on speakers and booking fees, please visit the conference webpage.

Registration closes 1 May 2019.

Our research fellow Raluca Soreanu is giving a plenary talk at the 11th Meeting of the International Society of Psychoanalysis and Philosophy.

Raluca will be talking on ‘Truth, Utopia and the Figure of the Child: A Ferenczian View.’ The meeting will be in Stockholm from 2-4 May, 2019.

For more information, visit the ISPP website.

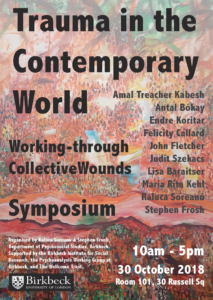

Our research fellow Raluca is organising a symposium at Birkbeck at the end of the month, and our PI Lisa will be contributing.

The symposium is being held at the Department of Psychosocial Studies and and will take place on 30 October, 2018, 10am to 5pm.

Room 101, 30 Russell Square, London WC1B 5DT

The symposium aims to create a space for an interdisciplinary conversation on the psychic transmission of trauma, on collective trauma and social mourning. While some voices argue that the notion of ‘trauma’ is overused and overstretched, we will explore the ways in which crucial aspects of both psychic life and social life can be formulated precisely as a trauma theory. What kind of metapsychological revisions are needed for a trauma theory for the contemporary world? What is the place of psychic splitting in making sense of social trauma? Or, in other words, what is the connection between the life of psychic fragments and the life of social fragments? How can we understand scenes of reliving the trauma, which take place in the streets and in the squares? How are institutions (including the state) implicated in social mourning, or, on the contrary, in its interruption? By asking these questions, we aim to illuminate the ways in which a revised trauma theory that takes into account the collective dimension of life is also a social theory.

The second part of the symposium will be dedicated to a discussion of Raluca Soreanu’s recent book Working-through Collective Wounds: Trauma, Denial, Recognition in the Brazilian Uprising (Palgrave, 2018). Soreanu argues for a phenomenology of psychic splitting, where we can follow, in a collective frame, what different psychic fragments ‘do’, or what becomes of their social life. Some psychic fragments are involved in the denial and the repetition of traumatic violence. Other psychic fragments are involved in the act of recognition or in a form of radical mutuality. A panel of psychoanalysts, psychosocial scholars and social theorists will discuss the implications of the ideas that Working-through Collective Wounds proposes, including notions such as: the confusion of tongues between registers of the social, memory-wounds, Orphic socialities, and traumatic voracity. Ultimately, the book brings into focus a creative and symbolising crowd, able to mourn and to preserve itself and things that matter in moments when extreme traumatic violence rips through the social body.

For more details, contact Raluca r.soreanuATbbk.ac.uk

Laura Salisbury, one of our PIs, is giving a keynote lecture at the Beckett & Technology Conference at Charles University, Prague, 13-15 September.

For full details of the conference, including the other keynote speakers, and information on how to register, please visit the conference website.

Our Exeter PI, Laura will be giving a paper on waiting and ‘grey time’ in Beckett at the Grey on Grey Conference at the University of Oslo, 22-23 May 2018.

Abstract:

There is a well-known story that when Beckett got to see the colour footage of his television play Quad played back on a black and white monitor he insisted it was ‘marvellous, […] 100,000 years later’. Beckett went on to record a monochrome, slowed down version of the play, Quadrat II, to sit alongside alongside the surprisingly colourful, rhythmic jerks and swerves of Quadrat I; together these snapshots of life represent an asymptotic stretching of time, a shuffling on and off towards a final still state. This seems like a typical move from the Beckett who insisted on policing the greyscale of his drama. ‘Too much colour’, he told the actor Billie Whitelaw, over and over, as she rehearsed Footfalls. Grey, or ‘Light black. From pole to pole’, is of course everywhere in Beckett’s later work, but although there has been some significant research on Beckett’s relationship to and with colour, the grey so firmly associated with Beckett’s aesthetic – from the tableaux of the plays to his iconic personal

image — has less frequently been linked to the author’s particular interest in the temporality of waiting. This paper sets out to determine what might be meant by ‘grey time’ in Beckett’s work. It traces out a time that is resolutely not a twilight or the famous l’heure bleue stretch of gloaming between night and day; it is rather, I argue, a historically specific, postwar articulation of temporality in which waiting is denuded of its ‘for’ – its purpose, its project, its

‘colour’. By showing how and why certain aspects of grey time speak clearly to Beckett’s ashen historical period, I also want to suggest which parts of Beckett’s temporality remain, lingering and enduring within our current waiting times.

For full details on the conference, including a list of speakers and their abstracts, visit Gray on Gray at the UiO: Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and and Ideas webpage.