Early July took the team to a two-day symposium called Why Care at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Berlin, which we ended up co-hosting. The invitation came from Benjamin Lewis Robinson and Birkan Tas, both former fellows on the Errans, in Time project that ran at ICI from 2016-18. Although the focus for this symposium was firmly on care – on the political and ethical challenges that it presents in relation to the increasing regulation, management, and indeed failures of care of all sorts – their own work has developed within an ICI project called Errans. This has used the figure of ‘erring’ as a kind of methodological procedure (erring as in to err, to make an error, to deviate, to fail…) to open up concepts like ‘environs’, ‘tensions’, ‘time’. What is an ‘erring’ in time? That’s a question that the Waiting Times team is really interested in. And when time errs (deviates, gets stuck, becomes suspended, fails to unfold), then what happens to care? Given how much overlap there was between their concerns and ours, we decided to co-host, and five of the team members went to Berlin to take part in a collection of keynotes, panels and discussions.

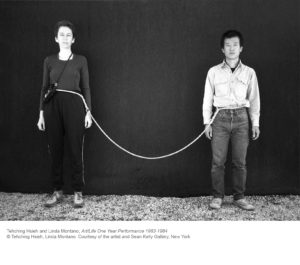

For the evening keynote on the Thursday night, I gave a talk (On Time, Care, and Not Moving On – and available to watch here) which introduced my book Enduring Time (Bloomsbury, 2017) and some thoughts on the work of the performance artist Merle Ladermann Ukeles, whom I interviewed back in 2016. Ukeles’ work is right at the heart of our discussions about the relation between time and care. She engages in the ‘female’ work of social reproduction –birthing and raising children, caring for people and things, cleaning, maintaining households and communities, and sustaining connections more generally – as a kind of laborious artwork that goes on for decades, so that it oddly it turns back into ‘work’ via ‘artwork’ (there is clearly labour in it), and hence a valued set of social practices, but without linking it with either the future time that is locked into the ‘product’ or the time of development (the development of others, that is) that is always devalued as ‘female’ time. In doing so, she reconfigures the relationship between time, care and gender, freeing up ‘maintenance’ as a kind of care practice available to all.

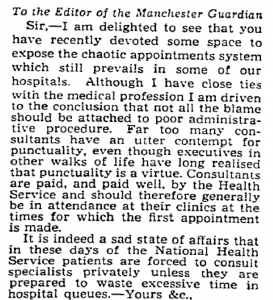

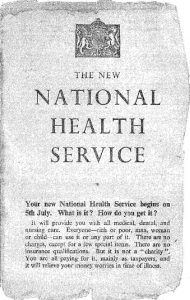

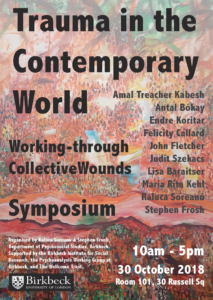

The next morning, Laura Salisbury, Deborah Robinson, Raluca Soreanu, Martin Moore and I convened a panel on ‘Waiting Times’ in which we pre-circulated papers to one another and then worked in rotation to summarize a colleague’s paper and raise a question about it, before moving on round the circle. Laura and I wrote on ‘Depressing Time’, which looked at the relationship between modernist ideas about waiting and depression, drawing on the phenomenological psychiatry literature and contemporary accounts of psychoanalytic practices of care. Raluca wrote on the work of Sandor Ferenczi, breaking down his different ways of understanding psychic time into ‘the tangent’, ‘the segment’ and ‘the meandering line’. Martin gave an account of his initial historical research into what it might have meant to wait in the early UK National Health Service.

Some things emerged that we’re still thinking through together. First, what does care have to do with ‘thirdness’? This term emerges from relational psychoanalysis to try to describe the way that care doesn’t flow simply from one to another, but is mediated by a third term (or the co-creation of a third relational entity) that takes us beyond the ‘doer and done to’ dynamics that Jessica Benjamin identified in The Bonds of Love. Raluca talked of how the psychoanalytic encounter creates something new which we don’t own, and we can’t fully control, that exists beyond the two but is used actively in the therapy, and constitutes acts of recognition and witnessing. Psychoanalytic care involves a systematic technical effort to hold yourself across different threads of time – a kind of ‘doing time’ in which time is always a verb. The presence of these multiple threads in the same moment of the analytic session is particular to psychoanalytic work. Waiting, from this perspective is less about waiting for, and more about waiting with, which Laura identifies as a key modernist temporality (think of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot). Raluca’s work, in particular, argues that the Budapest school of psychoanalysis offers a way to understand ‘a true third’ that is the work of analogy (one set of relations has a relation to another set of relations, and this creates something else, a third set of relations). This idea of thirdness could relate, however, to institutions where care takes place, such as the NHS, or the art gallery, that also mediate relations of thirdness that could be thought about as practices of care. Deborah, in particular, took up this idea of the art gallery or space as a third space where care can circulate.

Some things emerged that we’re still thinking through together. First, what does care have to do with ‘thirdness’? This term emerges from relational psychoanalysis to try to describe the way that care doesn’t flow simply from one to another, but is mediated by a third term (or the co-creation of a third relational entity) that takes us beyond the ‘doer and done to’ dynamics that Jessica Benjamin identified in The Bonds of Love. Raluca talked of how the psychoanalytic encounter creates something new which we don’t own, and we can’t fully control, that exists beyond the two but is used actively in the therapy, and constitutes acts of recognition and witnessing. Psychoanalytic care involves a systematic technical effort to hold yourself across different threads of time – a kind of ‘doing time’ in which time is always a verb. The presence of these multiple threads in the same moment of the analytic session is particular to psychoanalytic work. Waiting, from this perspective is less about waiting for, and more about waiting with, which Laura identifies as a key modernist temporality (think of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot). Raluca’s work, in particular, argues that the Budapest school of psychoanalysis offers a way to understand ‘a true third’ that is the work of analogy (one set of relations has a relation to another set of relations, and this creates something else, a third set of relations). This idea of thirdness could relate, however, to institutions where care takes place, such as the NHS, or the art gallery, that also mediate relations of thirdness that could be thought about as practices of care. Deborah, in particular, took up this idea of the art gallery or space as a third space where care can circulate.

Secondly, we thought through questions of mourning and lamentation that are embedded in the etymology of the term ‘cara’ (trouble, grief, sickness, think of ‘what is this life, if full of care’, from William Henry Davies’s poem ‘Leisure’, where care means difficulty). We thought together about how difficult it is to describe the quality of time as we feel it in the body, and the way that the granular surface of the symptom – depression for instance – has to be observed, described and looked at in a phenomenological way. Our engagement with Eugene Minkowski’s early phenomenological psychiatry offers a way to do this. But lamentations also came up around the 70th birthday of the NHS and participants in a workshop that Martin and Michael ran, expressing the wish to take care of it as an institution. ‘What has happened to ‘our’ NHS?’, is a constant cry. Martin’s historical work on the NHS reveals that it has always been in ‘crisis’. It was very fragile in the early days and didn’t gain some kind of solidity until it was shown to be cost effective in the 1950’s. What this helps to show up is how although the NHS is still seen to be expensive, there is now a sense that it is running out of time. Austerity creates new circumstances that challenge the ‘third space’ the NHS offers. You will be seen, but at a pace you have no control over.

Secondly, we thought through questions of mourning and lamentation that are embedded in the etymology of the term ‘cara’ (trouble, grief, sickness, think of ‘what is this life, if full of care’, from William Henry Davies’s poem ‘Leisure’, where care means difficulty). We thought together about how difficult it is to describe the quality of time as we feel it in the body, and the way that the granular surface of the symptom – depression for instance – has to be observed, described and looked at in a phenomenological way. Our engagement with Eugene Minkowski’s early phenomenological psychiatry offers a way to do this. But lamentations also came up around the 70th birthday of the NHS and participants in a workshop that Martin and Michael ran, expressing the wish to take care of it as an institution. ‘What has happened to ‘our’ NHS?’, is a constant cry. Martin’s historical work on the NHS reveals that it has always been in ‘crisis’. It was very fragile in the early days and didn’t gain some kind of solidity until it was shown to be cost effective in the 1950’s. What this helps to show up is how although the NHS is still seen to be expensive, there is now a sense that it is running out of time. Austerity creates new circumstances that challenge the ‘third space’ the NHS offers. You will be seen, but at a pace you have no control over.

But the question remains, what it means to want to protect it, what kind of cultural fantasy does it hold? This took us to a discussion of Melanie Klein’s work in Laura and my joint paper on depression, where the capacity to care for what we have, in fantasy, harmed is a certain kind of precarious psychic state. Care linked to grief and care as trouble and difficulty somewhat shifts the idea of being able to take care of the institutions that are tasked with caring for us.

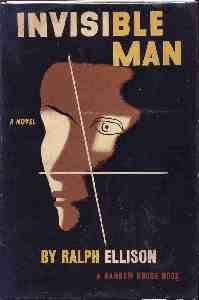

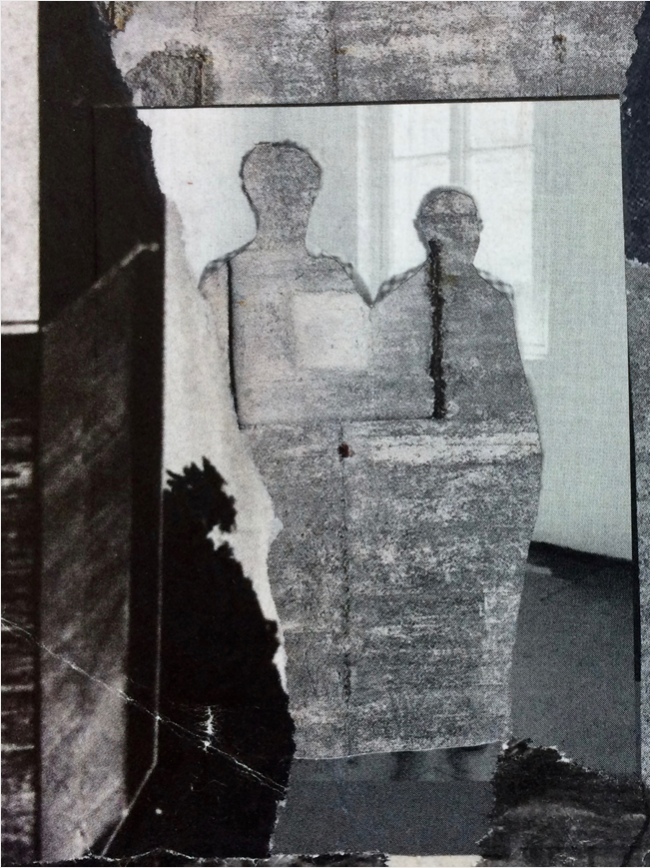

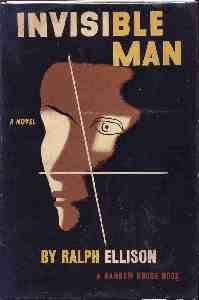

Finally, we thought about the giving of time as a form of taking care of the other that can’t be read in a straight forward way. Deborah talked about those who are ill and those who offer care and the ways that these interactions become the source of an artwork. Visual imagery and sound contain the intimacy of those conversations, raising questions about how to care for those images. Her work involves ‘thinking in darkness’ – working literally in the dark to select fames of film and then re-film them, using material from one temporal realm and transferring it to another (the gallery). Is there an aesthetics, then, of care, and can it take place in the gallery? Wilfred Bion talks about psychoanalytic attention as a ‘beam of darkness, a reciprocal of the searchlight’, which inverts the idea of thinking shining light on darkness. How rather does darkness, as a beam, intervene in light, and in what sense is this a careful practice? Thinking with Ellison’s Invisible Man, invisibility, after all, gives you a slightly different sense of time, of being behind the beat or in front of it, but not ‘in time’. Elizabeth Freeman’s notion of the deviant pause of sexual practices within the normative community does the same work here. In her presentation later in the symposium, Laura also noted how the slow reading the ‘perverse’ rhythms of Beckett’s prose work seem to demand elicits forms of attention, which are potentially careful, to the weight of the world. Such practices produce care as a different or queer way of thinking, or making sense, without sense appearing as prior to knowledge. We are always disrupted, after all, by the time of the other.

Finally, we thought about the giving of time as a form of taking care of the other that can’t be read in a straight forward way. Deborah talked about those who are ill and those who offer care and the ways that these interactions become the source of an artwork. Visual imagery and sound contain the intimacy of those conversations, raising questions about how to care for those images. Her work involves ‘thinking in darkness’ – working literally in the dark to select fames of film and then re-film them, using material from one temporal realm and transferring it to another (the gallery). Is there an aesthetics, then, of care, and can it take place in the gallery? Wilfred Bion talks about psychoanalytic attention as a ‘beam of darkness, a reciprocal of the searchlight’, which inverts the idea of thinking shining light on darkness. How rather does darkness, as a beam, intervene in light, and in what sense is this a careful practice? Thinking with Ellison’s Invisible Man, invisibility, after all, gives you a slightly different sense of time, of being behind the beat or in front of it, but not ‘in time’. Elizabeth Freeman’s notion of the deviant pause of sexual practices within the normative community does the same work here. In her presentation later in the symposium, Laura also noted how the slow reading the ‘perverse’ rhythms of Beckett’s prose work seem to demand elicits forms of attention, which are potentially careful, to the weight of the world. Such practices produce care as a different or queer way of thinking, or making sense, without sense appearing as prior to knowledge. We are always disrupted, after all, by the time of the other.

Image Credit © Claudia Peppel, collage (detail)

Some things emerged that we’re still thinking through together. First, what does care have to do with ‘thirdness’? This term emerges from relational psychoanalysis to try to describe the way that care doesn’t flow simply from one to another, but is mediated by a third term (or the co-creation of a third relational entity) that takes us beyond the ‘doer and done to’ dynamics that Jessica Benjamin identified in The Bonds of Love. Raluca talked of how the psychoanalytic encounter creates something new which we don’t own, and we can’t fully control, that exists beyond the two but is used actively in the therapy, and constitutes acts of recognition and witnessing. Psychoanalytic care involves a systematic technical effort to hold yourself across different threads of time – a kind of ‘doing time’ in which time is always a verb. The presence of these multiple threads in the same moment of the analytic session is particular to psychoanalytic work. Waiting, from this perspective is less about waiting for, and more about waiting with, which Laura identifies as a key modernist temporality (think of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot). Raluca’s work, in particular, argues that the Budapest school of psychoanalysis offers a way to understand ‘a true third’ that is the work of analogy (one set of relations has a relation to another set of relations, and this creates something else, a third set of relations). This idea of thirdness could relate, however, to institutions where care takes place, such as the NHS, or the art gallery, that also mediate relations of thirdness that could be thought about as practices of care. Deborah, in particular, took up this idea of the art gallery or space as a third space where care can circulate.

Some things emerged that we’re still thinking through together. First, what does care have to do with ‘thirdness’? This term emerges from relational psychoanalysis to try to describe the way that care doesn’t flow simply from one to another, but is mediated by a third term (or the co-creation of a third relational entity) that takes us beyond the ‘doer and done to’ dynamics that Jessica Benjamin identified in The Bonds of Love. Raluca talked of how the psychoanalytic encounter creates something new which we don’t own, and we can’t fully control, that exists beyond the two but is used actively in the therapy, and constitutes acts of recognition and witnessing. Psychoanalytic care involves a systematic technical effort to hold yourself across different threads of time – a kind of ‘doing time’ in which time is always a verb. The presence of these multiple threads in the same moment of the analytic session is particular to psychoanalytic work. Waiting, from this perspective is less about waiting for, and more about waiting with, which Laura identifies as a key modernist temporality (think of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot). Raluca’s work, in particular, argues that the Budapest school of psychoanalysis offers a way to understand ‘a true third’ that is the work of analogy (one set of relations has a relation to another set of relations, and this creates something else, a third set of relations). This idea of thirdness could relate, however, to institutions where care takes place, such as the NHS, or the art gallery, that also mediate relations of thirdness that could be thought about as practices of care. Deborah, in particular, took up this idea of the art gallery or space as a third space where care can circulate. Secondly, we thought through questions of mourning and lamentation that are embedded in the etymology of the term ‘cara’ (trouble, grief, sickness, think of ‘what is this life, if full of care’, from William Henry Davies’s poem ‘Leisure’, where care means difficulty). We thought together about how difficult it is to describe the quality of time as we feel it in the body, and the way that the granular surface of the symptom – depression for instance – has to be observed, described and looked at in a phenomenological way. Our engagement with Eugene Minkowski’s early phenomenological psychiatry offers a way to do this. But lamentations also came up around the

Secondly, we thought through questions of mourning and lamentation that are embedded in the etymology of the term ‘cara’ (trouble, grief, sickness, think of ‘what is this life, if full of care’, from William Henry Davies’s poem ‘Leisure’, where care means difficulty). We thought together about how difficult it is to describe the quality of time as we feel it in the body, and the way that the granular surface of the symptom – depression for instance – has to be observed, described and looked at in a phenomenological way. Our engagement with Eugene Minkowski’s early phenomenological psychiatry offers a way to do this. But lamentations also came up around the  Finally, we thought about the giving of time as a form of taking care of the other that can’t be read in a straight forward way. Deborah talked about those who are ill and those who offer care and the ways that these interactions become the source of an artwork. Visual imagery and sound contain the intimacy of those conversations, raising questions about how to care for those images. Her work involves ‘thinking in darkness’ – working literally in the dark to select fames of film and then re-film them, using material from one temporal realm and transferring it to another (the gallery). Is there an aesthetics, then, of care, and can it take place in the gallery? Wilfred Bion talks about psychoanalytic attention as a ‘beam of darkness, a reciprocal of the searchlight’, which inverts the idea of thinking shining light on darkness. How rather does darkness, as a beam, intervene in light, and in what sense is this a careful practice? Thinking with Ellison’s Invisible Man, invisibility, after all, gives you a slightly different sense of time, of being behind the beat or in front of it, but not ‘in time’. Elizabeth Freeman’s notion of the deviant pause of sexual practices within the normative community does the same work here. In her presentation later in the symposium, Laura also noted how the slow reading the ‘perverse’ rhythms of Beckett’s prose work seem to demand elicits forms of attention, which are potentially careful, to the weight of the world. Such practices produce care as a different or queer way of thinking, or making sense, without sense appearing as prior to knowledge. We are always disrupted, after all, by the time of the other.

Finally, we thought about the giving of time as a form of taking care of the other that can’t be read in a straight forward way. Deborah talked about those who are ill and those who offer care and the ways that these interactions become the source of an artwork. Visual imagery and sound contain the intimacy of those conversations, raising questions about how to care for those images. Her work involves ‘thinking in darkness’ – working literally in the dark to select fames of film and then re-film them, using material from one temporal realm and transferring it to another (the gallery). Is there an aesthetics, then, of care, and can it take place in the gallery? Wilfred Bion talks about psychoanalytic attention as a ‘beam of darkness, a reciprocal of the searchlight’, which inverts the idea of thinking shining light on darkness. How rather does darkness, as a beam, intervene in light, and in what sense is this a careful practice? Thinking with Ellison’s Invisible Man, invisibility, after all, gives you a slightly different sense of time, of being behind the beat or in front of it, but not ‘in time’. Elizabeth Freeman’s notion of the deviant pause of sexual practices within the normative community does the same work here. In her presentation later in the symposium, Laura also noted how the slow reading the ‘perverse’ rhythms of Beckett’s prose work seem to demand elicits forms of attention, which are potentially careful, to the weight of the world. Such practices produce care as a different or queer way of thinking, or making sense, without sense appearing as prior to knowledge. We are always disrupted, after all, by the time of the other.