Martin Moore reports from the field …

The European Association for the History of Medicine and Health held its biennial conference in Birmingham on August 27-30th, an event at which both Michael J Flexer and I were lucky enough to speak. Under the theme of “sense and nonsense”, the conference brought together scholars from around the globe to explore the emerging field of sensory history, covering topics as diverse as smell and health in the art of the Dutch Golden Age to the introduction of cocaine into China at the turn of the twentieth century.

The first paper from the Waiting Times’ team came on the morning of Thursday 29th from Michael, as part of the Senses and Modern Health/Care Environments network led by Dr Victoria Bates. As usual, Michael’s paper was a tour de forceof wit and insight, and generated some of the more interesting summaries on the Twitter once divorced from context…

Michael’s exploration of the semiotics of contemporary general practice waiting rooms provoked lively discussion, not least around how such spaces were reworked by contemporary political economies and moments of resistance to intended use.

However, two aspects of the paper stuck out for me.

The first was the way in which Michael deconstructed the concept of “sense” through Deleuze, pointing out that many individual aspects of the waiting rooms had anticipated user needs but generally failed to come together cohesively to make sense as a whole. The accumulation of relics (defunct signs of varied sizes, old magazines), unintentional juxtapositions (advertising social care for the elderly on a space reserved for infant welfare concerns), and perhaps even interrupted efforts to “dress” the space created a sense of incoherence, taking patients out of the “now” and scattering them throughout time (and space).

The second was the total absence of the general practitioner from the waiting room.

Responding to a question drawing on contrast with the premises of German GPs, Michael noted that these spaces almost consciously removed the doctor’s personality. In many respects, this absence emerged from contemporary structures of ownership, where GPs likely work in – rather than own – the spaces in which they practice. Indeed, this divorce created situations where doctors could not explain the presence of certain leaflets in their waiting rooms, nor could practice managers. Agreements were made to advertise certain products or services at the Commissioning Group level, and so the spaces of waiting would be subject to reshaping at the level of management rather than labour.

Both these points caused me to reflect on my own work, and on the specific history of general practice care in Britain.

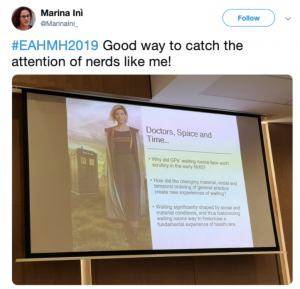

My paper (delivered on the Thursday afternoon) looked to explore why GPs began to pay so much attention to their waiting rooms during the 1950s and 1960s, and how the changes being pioneered at this time reworked the sociality and sensory experience of waiting for primary healthcare. In this I began to consider some of the unintended consequences of certain changes, such as the use of public information notices, and here historical echoes with Michael’s considerations emerged. (For instance, how posters demanding patients be responsible for managing one’s own time, as well as that of the doctors, could ironically create a sense of disempowerment and distance from moments of care.)

It also deployed some rather cheap tricks to keep the audience interested…

However, what Michael’s paper made me appreciate were the ways in which structures of ownership could influence how waiting was shaped and experienced. Although the creation of the NHS removed formal “ownership” from GPs in that practices could no longer be bought or sold as private property, GPs nonetheless controlled how their practices were laid out and interiors designed. At least in the 1950s and 1960s, GPs largely determined how the time of waiting was passed – what patients were exposed to, and how they were held.

Of course, patients found ways to disrupt the best plans of doctors, such as damaging furnishings or removing materials from the premises, whilst the chatter that might pervade waiting rooms could hardly be legislated for or controlled if patients were determined. (Indeed, based on Michael’s observations, waiting in general practice may well have been more communal in the post-war decades, reflecting changing lengths of waiting, the number of patients in the waiting room and broader cultural practices of waiting in public spaces.)

Moreover, Michael’s references to how a space could be made “nonsensical” by the sediment of previous layouts or interrupted actions also underlined how I may have previously placed too much emphasis on the coherence of GPs’ plans for redecoration; in situ, and longitudinally, their decisions may have made less sense than intended.

Nonetheless, the contrast between our papers drove home how the aggregation of practice organisation since the 1990s, and particularly the 2000s, may well have altered the waiting experience for patients.

Beyond our panels, there were several personal highlights from the event.

The panel on “Modern Medical Visions” featuring Beatriz Pichel, Kat Rawling, and Harriet Palfreyman offered eye-opening (apologies for the pun) explorations of the way that photographs and drawings provided multiple modes of viewing patients and illnesses throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and underlined how such materials functioned in multi-sensory and experimental ways.

It also featured original artwork (can you guess which one is the creation of a medical artist?):

Claire Hickman’s discussion of birds and the therapeutic hospital environment was another paper that made me think about temporalities in new ways, and particularly the affective and psychological relations produced by asynchronous life-spans. (Although the absence of a “late parrot” was disappointing.)

However, perhaps the most invigorating – and humbling – paper came from Tracey Loughran’s keynote, which explored gendered and embodied time through women’s memories and experiences of menstruation.

The paper stressed the importance of historicising the body, placing it in shifting cultural and social contexts, whilst also not denying the embodied-ness of historical subjects. It thus raised important questions about how we might think about the ways that changing expertise and technologies around reproduction, conception and menstrual cycles have mediated women’s experiences of embodied time, establishing different norms, expectations, and practices across generations.

In addition, though, Loughran also queried the multiple temporal entanglements of doing historical research, and she ended her keynote reflecting on the embodied experience of being a female historian. She castigated those male academics who wasted their female colleagues’ time with self-indulgent – and ignorant – “more of a comment than a question” interventions, and who often took the same approach in everyday working life. She also called for female academics to resist pressures to take up less time and space, and to remind them that they were the future.

It was a powerful clarion call, and one which will definitely live long in the memory.

All in all, then, the conference was a fantastic – if somewhat exhausting – four days. It was intellectually enriching and raised politically vital issues. The University of Birmingham provided a great venue for the event, and my generous local guides made me appreciate the city much more than I had previously.

My only regret was that I was unable to attend every panel, with many running simultaneously. Well, that and the fact that there was no karaoke. Fittingly, I suppose my wait to sing “Time After Time” goes on …