Whether in pop culture or academic work, time and space have often been inextricably linked. Though the Waiting Times team has been thinking about temporality in ways that breaks – or at least complicates – this connection, one space that I have been thinking about recently has been the general practice waiting room.

The waiting room as an historical space

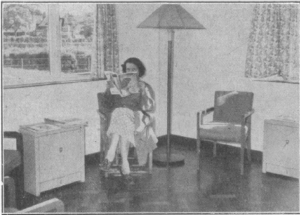

As work by the Cultural Histories of the NHS project suggests, contemporary experiences and associations of NHS waiting are often shaped by its material elements, not least the chairs and signs that populate its waiting rooms.

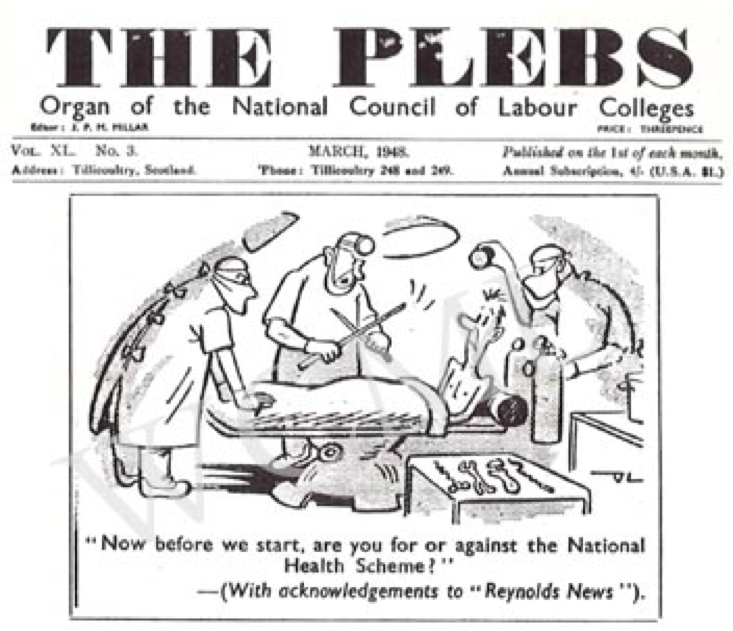

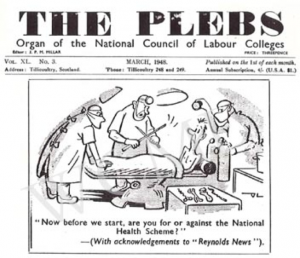

The work I have been doing has been to consider how such spaces and associations came to be. Much like the medical appointment, the waiting room is an historical construction. It is a space which only began to receive sustained public attention in Britain with the collectivisation of healthcare funding under National Health Insurancein 1913, and which practitioners only began to think about substantively following the creation of the health service after 1948.

The creation of the NHS was particularly important, with the removal of insurance principles or payment barriers increasing the demand on premises that had not been designed to hold large numbers of patients: many practices in 1948 were in small converted shop premises or in a GP’s house. The latter might have the dining room as a waiting area, but patients waiting outside either type of premises was not uncommon.

The NHS also made criticisms of health services a problem for central government – leading politicians to apply pressure for reform – as well as drawing much firmer lines between general practice and hospital practice, forcing GPs to think about how to distinguish themselves professionally.

The post-war settlement and the waiting room

The way that the NHS brought attention to the waiting room often meant that discussions were framed in relation to the promises of – and discontents with – what some historians refer to as the post-war settlement.

With regards to healthcare, elite practitioners and organised professional bodies like the British Medical Association had opposed the NHS as conceived by the Labour government in 1948. Among other things, they feared that state employment would result in a loss of income, professional freedom, and unmediated professional-patient relationships.

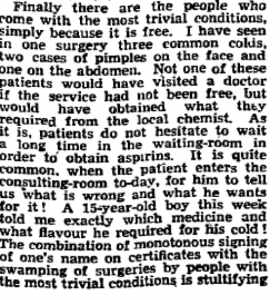

GPs in particular continued to criticise the new service into the early 1950s.

Some complained about a loss of class deference and professional status, of being treated by patients as servants or ‘suppliers of medicines’ rather than as a medical advisers or even as friends.

They also argued that, by removing financial barriers to care, the NHS created demanding and entitled patients. Patients would allegedly enter the consulting room ‘‘to tell us what is wrong and what [they] want for it’.

These anxieties about status and the shifting relations of medicine were played out in discussions of waiting rooms.

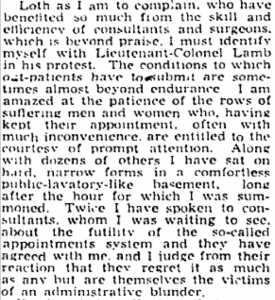

Reports were sent to central government departments about patients who would ‘tear out pages of periodicals in the waiting room, grind sticky sweets into the carpet, take cushions, and even carve their initials on the furniture’. One GP appealed to the Ministry of Health to make ‘it quite clear to the general public that a doctor’s waiting-room is not a place of public entertainment, but rather a place where people are expected to behave with a certain amount of respect and decorum’.

The focus on patient behaviour and deference was indicative of the class-bound anxieties of some GPs, many of whom would have previously had separate entrances and waiting spaces for private patients and those receiving publicly-funded care. No longer able to segregate their patients, some doctors were still so concerned about working class patients bringing dirt into waiting rooms that they even used interior design to prevent ‘greasy heads’ marking walls, and praised the durability of flooring to stand up to workmen’s boots.

Supplement to the British Medical Journal, 6 November 1954

The challenges of writing histories of the waiting room

There is still much to explore about how waiting rooms were thought about and redeveloped over the twentieth century. However, researching the subject so far has not proven straightforward.

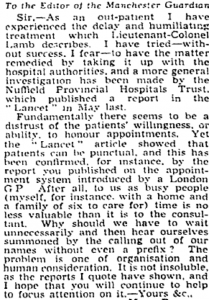

Methodologically, I have faced problems familiar to many social and cultural historians. The “archives” of general practice waiting rooms are hardly substantial, and have been largely created or curated by medical professionals, civil servants, and media editors. Equally, their materials are predominantly composed of digressions about waiting rooms made in discussions about other topics, or are made up of complaints that reveal expectations and social norms only by their absence or negation.

The dominance of complaints from “establishment” groups, however, has also posed other challenges, causing me to reflect on my own subjectivity and affective responses to sources.

As a social historian, I share my field’s political and intellectual sympathies to histories of marginalised groups, as well as its critical disposition to power and professional self-interest. Likewise, as someone who has grown up with – and been a long-term beneficiary of – the NHS, I have been interpellated by its core ideals (if not lived practice) of universal healthcare, free at the point of use.

As a result, GPs’ grievances initially struck me as exaggerated, underpinned by a sense of superiority to patients, and indicative of an opposition to any form of egalitarianism from professionals with considerable class privilege.

Indeed, surveys conducted at the time provided some support for this reading, with one prominent medical observer noting that ‘some general practitioners are so easily irritated by such an attitude [of entitlement and lack of respect among patients] that they are apt to think it more widespread than it actually is’.

My first engagement with these materials, therefore, was to read criticisms primarily for the way they provided insight to the reception of the post-war welfare state, and for the strategic purpose the played inprofessional and political projects.

Nonetheless, further exploration and consideration has brought home the importance of maintaining critical reflection on my own subjectivity and affective responses.

Historically, it was not just doctors who were sceptical or anxious about the NHS. State provision had not been welcomed by everyone.[1] For instance, though many were quickly convinced of the NHS’s advantages, a significant proportion of the British public were initially concerned about the potential loss of ‘the personal touch’ in state-funded medicine.

Moreover, though there is a clear element of performativity in GPs’ complaints, in reading them differently I have also begun to tease out insights into the culture of the early health service – the way its proposed radicalism was filtered through inherited buildings and beliefs, the presumptive middle-class norms behind ideas of universality, and the ways that attitudes towards patients were slowly built into the very fabric of the service.

Even more varied readings are possible, ones that might reveal more about the everyday life of post-war Britain. Complaints about demanding patients, for example, could provide insight into the complexities of the psychological life of traditional middle-class groups in a period of rising affluence but concern about relative decline. Similarly, reading discussions about nailed boots and greasy heads for indicators of patient behaviour might generate insight into the changing nature of work and housing, or shifting social norms about self-presentation in public spaces, if read over time.

However, changing the way I engage with sources and the questions I ask has required more than a change in methodology or conceptualisation.

I have had to maintain an awareness of my own position in academic and political fields. I have had to reflect on how my work has been informed by my own psychological investments in the NHS and its proposed values, as well as by my attachment or critical disposition towards certain professional groups.

Of course, undertaking practices of self-reflection is not the same as striving for “objectivity”, or somehow overcoming my position as an historically-formed subject. Instead, it is to realise that a critical disposition towards the historian’s subjectivity can open up new questions and new avenues for research.

Who would have thought that even just thinking about waiting rooms (rather than being forced to wait within one) could encourage such existential questions? (Bergson, put your hand down – no-one likes a show-off.)

Dr Martin Moore is the historian on the Waiting Times project.

Notes

[1]For more in depth analyses, see work by Nick Hayes: https://academic.oup.com/ehr/article/CXXVII/526/625/438109. And Andrew Seaton: https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/article/26/3/424/2451908.